The Political Fix: Will BJP’s ‘insider trading’ in the Bihar elections leave Nitish Kumar stranded?

What you need to know about the upcoming Bihar polls.

Welcome to The Political Fix by Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, a newsletter on Indian politics and policy. To get it in your inbox every week, sign up here.

We don’t charge for this newsletter, but if you would like to support us consider contributing to the Scroll Reporting Fund or, if you’re not in India, subscribing to Scroll+.

The Big Story: Bihar battle

How do you convey just how much of a roller-coaster the 2015 Bihar election was? Start by looking back at just the drama on election day on NDTV, a relatively sober news channel by Indian TV standards.

By 9 am, the channel had called the election for the Bharatiya Janata Party, which had been up against the “mahagathbandhan” – the Grand Alliance of the Rasthriya Janata Dal, the Congress and the BJP’s former partner, the Janata Dal United.

Those three parties had teamed up to take on the BJP juggernaut under Prime Minister Narendra Modi. And here was NDTV saying, at the start of the day, that this grand effort failed.

Ultimately it did – but not in the way the channel reported it.

Results coming in soon after that 9 am declaration made it clear that NDTV got it wrong, and that the grand alliance had actually delivered a solid drubbing to Modi’s BJP. The panel of eminent political analysts on the channel, who had been explaining why the Bihar voter had picked the BJP had to do an about-face.

As Mukul Kesavan wrote at the time, “Seldom has [Karl] Popper’s cynicism been more vividly borne out, live, on prime time than it was on Sunday morning. The same panel that had confidently explained defeat, now, given the benefit of hindsight, omnisciently explained victory. After such knowledge, what forgiveness?”

When the dust settled, the Grand Alliance had won 178 seats compared to just 58 for the BJP and its allies, in a state with 243 seats where 122 would be sufficient for a victory. Modi’s BJP, which had already failed to win in Delhi earlier that year, was now out of power in the the country’s third-most populous state, home to more than 100 million people.

Two years later, however, Chief Minister Nitish Kumar of the Janata Dal (United) decided to jump ship and return to his old alliance partners – burying the hatchet with Modi, nullifying the voter mandate for the grand anti-BJP grouping and putting the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance back in power in Bihar.

That is where things appeared to stand ahead of the 2020 elections, taking place amid the Covid-19 pandemic, with what in August seemed likely to be an extremely insipid electoral season despite Bihar’s status as one of the most politically fertile states in the country and after the limitations of the state government coming into sharp focus because of the migrant crisis following the coronavirus lockdown.

A BJP-JD(U) victory seemed a foregone conclusion, with the RJD-Congress Opposition appearing to lack energy or a narrative.

Over the last few weeks, one element of that calculation has been put to the test.

Bihar elections

Voting in three phases: October 28, November 3, November 7.

Results: November 10.

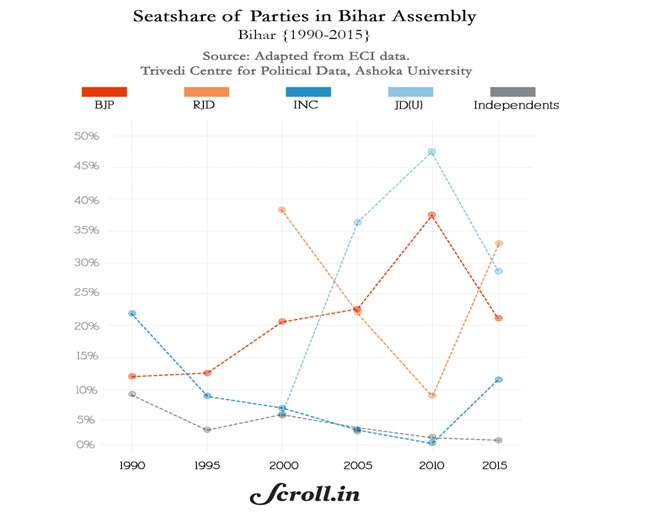

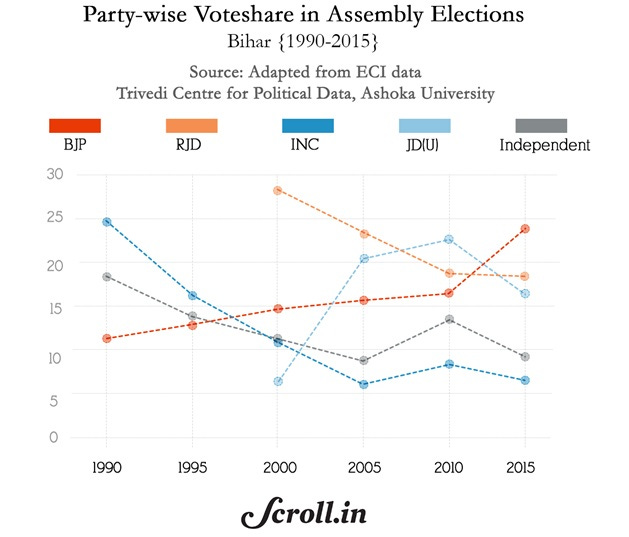

Charts from the Trivedi Centre for Political Data’s analysis of the results, in 2015.

One big question that came out of Nitish Kumar’s decision, in 2017, to break with the Grand Alliance and return to the BJP was what that would mean for his party. While the move allowed Kumar to remain chief minister – a post he has occupied almost continuously since 2005 – it also meant his party, the JD(U), would struggle to define itself while also facing anti-incumbency.

Kumar was once lauded as the face of development in a state that, along with Uttar Pradesh, has languished at the bottom of most indices of progress. Though his early years are credited with establishing law and order and the building of roads, data and anecdotal reports over the last few years are less flattering.

NITI Aayog’s various indices also offer a reminder of how the state continues to languish.

Bihar is dead last on the ranking of states by how successful they have been at achieving Sustainable Development Goals. It comes in at the 30th rank, out of 36, on the Aayog’s index of states by their export preparedness, a sign of how its industrial base remains tiny.

Every year, the state makes its way to the news because of the damage caused by widespread flooding. Its unemployment rate is well above the national average. Across, the board – whether you look at health indicators, economic factors or educational ones – Bihar continues to struggle, even though its Gross Domestic Product growth rate has been something of a bright spot.

M Rajshekhar’s thread offers some useful context.

The Covid-19 crisis also turned the spotlight on the state.

In July, the state was called out by the NITI Aayog for having the lowest tests per million of major states. It has since massively ramped up the number of tests it does, though questions have been raised about the reliability of the antigen tests that it predominantly uses.

But it was Modi’s hastily called national lockdown between March and May that really played out in a big way for Bihar. As millions of migrant workers began leaving their “host states” and returning home, Kumar made it clear that he did not want them back. Unlike Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Adityanath, who arranged for stranded labourers to be transported, Kumar said, “If five people come on the road and make demands, then should the government buckle?”

Eventually, once the Centre made belated arrangements for the migrants to return, reports suggested that as many as 32 lakh – 3.2 million people – traveled back to Bihar.

Soon after the state saw a huge jump in registration of job cards under the rural employment guarantee, and Modi chose Bihar to launch his re-packaging of existing employment schemes meant to provide employment to return migrants.

Some of this explains one unusual aspect of the upcoming election.

Nearly everyone expects the BJP-JD(U) alliance to win. And yet, many seem extremely unhappy with Nitish Kumar’s leadership.

The C-Voter opinion poll, for example, said that 56.7% of respondents were angry with Kumar’s government and wanted change. And 45.3% rated his performance as poor. And yet the poll predicted a comfortable 44.8% vote share going to the BJP-JD(U) combine, compared to just 33.4% to the RJD-Congress Opposition.

Angry with Kumar, yet not unhappy with Modi or the BJP-JD(U) government – especially since the RJD’s Tejashwi Yadav doesn’t seem to be offering much of a challenge. That seems to be the takeaway for the polls, and what many have reported from the state.

Ally vs Ally

Which is where the new calculation comes into play.

The Lok Janshakti Party, whose founder Union Minister Ram Vilas Paswan died last week, has been the BJP’s junior partner in Bihar since 2014. Over the last year, however, Paswan’s son – actor-turned-politician Chirag Paswan, who leads the party now – has been steadfast in its criticism of Chief Minister Nitish Kumar even though they are both members of the BJP’s National Democratic Alliance.

The party is small. It won just two seats in the assembly elections in 2015. But it has benefited from its partnership with the BJP, both electorally and in terms of stature, and has built its presence particularly among Dalits in the state.

On October 4, the Lok Janshakti Party announced that it would not be contesting the state elections in an alliance with Kumar’s party. Instead, it will put up candidates in 143 seats – happily taking on the Janata Dal (United) – with a promise not to contest against the BJP. Moreover, it remains an ally of the BJP’s at the national level.

What gives? Why is one alliance partner of the BJP taking on another alliance partner of the BJP in the state? And who stands to gain?

The response to that might actually combine the answers to the two other questions posed – what happens to Nitish Kumar and the Janata Dal (United) after he fled the Grand Alliance and returned to the BJP, and why do opinion polls seem to give the ruling coalition the win even though the chief minister is so disliked?

“This Patna paradox has produced a Patna consensus,” writes Shivam Vij. “In the politics-obsessed state of Bihar, people are sure Nitish Kumar will be booted out of the chief minister’s chair after the election – perhaps, after a few months of the result. The near certainty of this consensus is the political chatter helping people come to terms with the fact that they are going to be forced to vote for a chief minister they don’t like.”

In other words, despite BJP politicians insisting that they are contesting under the leadership of Nitish Kumar and making a show of being unhappy with the Lok Janshakti Party’s decision, the widespread belief is that the situation has been engineered by Modi’s party.

As Sankarshan Thakur writes,

“Officially, the BJP maintains allegiance to vows it has publicly made on Nitish’s continued chief ministership. It has also “warned” party men not to embrace the LJP and harm the prospects of Nitish’s candidates. But that warning comes with a pronounced wink. Several BJP leaders and sympathisers have already “left” to join the LJP and accepted poll tickets.”

If the BJP wins enough seats that it is able to form the government with the handful that the Lok Janshakti Party can bring in, will it ditch the unpopular Kumar, or at least insist on its own chief minister? Does Kumar, who was evidently hoping to rely on Modi’s popularity over his own to win, have any leverage to push back against this ‘insider trading’?

And what does it say about the Opposition that the biggest drama arising out of this Bihar election involves one BJP ally taking on another? Plus, on the off-chance that the Opposition actually does decently, are its leaders willing to partner once again with Kumar just to come to power?

With less than a month to go for results, an election that had seemed like a done deal is suddenly offering more drama, even if very little of that involves actually engaging with the challenges faced by a state that would be one of the 15 largest countries in the world by population if it weren’t in India.

Flotsam and Jetsam

If you missed the Scroll.in special report on the silent crackdown taking place in Delhi under the guise of investigating the riots, click here. And go read this interview with Apoorvanand, who has been targeted and questioned by police in the case:

“They are telling Muslims, don’t dare do this. You have no right to protest. If you go out then everything you do will be criminalised and you will be disabled for life. You will be ruined. This is the message they are trying to send to Muslim youth that we won’t allow you to have a political voice. You are not political subjects, you are not political agents in this country.”

Covid-19 Crisis: The number of new cases in India continues to come down from the mid-September peak, although that still means the country has registered more than 100,000 deaths. Despite the graph offering some hope, there are fears that the upcoming festive season – with Dussehra on October 25 and Diwali on November 14 – may bring with it a fresh spike.

GST Compensation mess: The national government promised to compensate states for lost revenue in return for agreeing to a country-wide Goods and Services Tax, but it now wants to renege on that promise because of the fiscal crisis caused by its handling of Covid-19. The Centre has alternated between good cop and bad cop, and on October 12 will once again attempt to find some sort of compromise while maintaining some semblance of cooperative federalism.

Judicial drama: Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister Jagan Mohan Reddy dropped a bombshell this week, writing to the Chief Justice of India alleging that Supreme Court judge Justice NV Ramana had been influencing the sittings of the state High Court and also claiming that cases important to the Opposition Telugu Desam Party were “allocated to a few judges”. Ramana is next in line to be Chief Justice of India, making the allegations – and the fact that they came from a chief minister – even more shocking.

Read Salil Tripathi’s tribue to Pushpa Bhave, a teacher, cultural critic, activist and “the embodiment of middle-class Mumbai”, who died last weekend at 81.

Can’t make this up

Of course, Coronavirus is going to turn up in Durga Puja pandals.

And what connects US President Donald Trump and Shah Rukh Khan?

Thanks for reading the Political Fix. If you enjoy this newsletter, please do share it. We’ll be back on Friday with a new Q&A. Send suggestions and feedback to rohan@scroll.