The Political Fix: Why India’s new Parliament building may spark a North-South tug-of-war

And why we need to discuss the delimitation question right away.

Welcome to The Political Fix by Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, a newsletter on Indian politics and policy. To get it in your inbox every week, sign up here.

We don’t charge for this newsletter, but if you would like to support us consider contributing to the Scroll Reporting Fund or, if you’re not in India, subscribing to Scroll+.

The Big Story: Foundational challenge

On December 10, Prime Minister Narendra Modi will lay the foundation stone for a new Parliament building in Delhi.

It might seem odd for the Political Fix to focus on what sounds like a fairly ordinary government photo-op on the same week that Modi will face a Bharat Bandh, a national strike, despite several rounds of talks with protesting farmer groups that have been demanding the repeal of agricultural laws passed two months ago (see last Monday’s issue for more on this).

The protests – partially blockading the roads leading into Delhi – have only grown more significant, as revealed by the government’s willingness to discuss amendments to the law to address the farmers’ concerns. The Indian Express reports that the government is even considering a special Parliament session to pass amendments, though the farmers have maintained their demand for a full repeal.

The government’s potential backtracking is reminiscent of its retreat from an attempt to alter pro-business land acquisition laws in Modi’s first term, a moment widely seen as part of the government’s pivot towards a more welfarist narrative that eventually helped it win a massive re-election in 2019.

It has yet to commit to any changes, but the fact that it is even in talks with the farmer groups stands in stark contrast to the government’s attitude towards the protests against the Citizenship Act amendments passed in 2019. Hundreds of thousands took to the streets to protest the discriminatory law around the country, only to be deemed anti-national by the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party, which unleashed police brutality against protesters in many cases.

So why are we discussing the laying of a foundation stone for a building instead?

Because of what is different about the new Parliament.

Leave aside questions of whether this is the right time for Modi’s amibitious and expensive Central Vista revamp, which aims to reconstruct the heart of India’s government in New Delhi to reflect his time in power. Never mind also the allegations of impropriety in awarding the contract for a new Parliament to the Tata Group, which were later withdrawn by a rival corporate house.

Full house

One key detail about the new building, as PTI reported: “In the new building, the Lok Sabha chamber will have a seating capacity for 888 members, while Rajya Sabha will have 384 seats for the upper house members…At present, Lok Sabha has a sanctioned strength of 543 members and Rajya Sabha of 245.”

If the Lok Sabha only has 543 members, why does its new chamber need 888 seats?

One answer, presumably, is the intention to allow the Lok Sabha to also host a full joint session, when members of both India’s upper and lower houses of Parliament sit together. This is done on special occasions, either to mark a significant date or in the case of an address by a visiting dignitary.

But joint sittings can also be called when there is a deadlock in terms of legislation between the two houses, usually allowing the party or coalition with larger support in the Lok Sabha to pass a bill – as has happened on less than a handful of occasions in the past.

The more relevant reason for the Lok Sabha to have more seats is simply that there are likely to be more Lok Sabha members.

The Indian Constitution permits a maximum of 552 Lok Sabha MPs. But the state-wise allocation of seats was supposed to be adjusted every 10 years based on population changes, in such a way that each Member of Parliament would represent roughly an equal number of people, not counting Union Territories or particularly small states.

That represented a problem particularly in the 1970s, when population control was an official objective of the Indian government. If seats were re-allocated as per the set formula, states where the population grew faster would be rewarded with more Lok Sabha MPs, while states that were successfully implementing the state policy of population control would effectively be penalised and lose seats.

‘Malapportionment’

To address this, the number of seats was frozen in 1976, with the aim of revisiting the matter after the 2001 census. In 2002, the delimitation exercise – the term used for re-evaluating constituencies – was again pushed off to 2026, now fast approaching, though it might have to wait until after the 2031 census.

From a democratic point of view, this is problematic, since it means that every Member of Parliament from Tamil Nadu represents on average 1.8 million citizens, whereas an MP From Uttar Pradesh represents 3 million – effectively increasing or decreasing the value of a vote depending on where you live.

Side note: Fascinatingly, Milan Vaishnav and Jamie Hintson found that despite 1.2 million fewer citizens on average per constituency in Tamil Nadu than Uttar Pradesh, the number of registered voters were about the same. Even more remarkably, more voters actually voted per constituency in Tamil Nadu than Uttar Pradesh.

However, from a political economy point of view, this postponement of the problem for 50 years is also challenging because, whenever the numbers are adjusted they will lead to a remarkable shift in power – which broadly breaks down on a North/South axis.

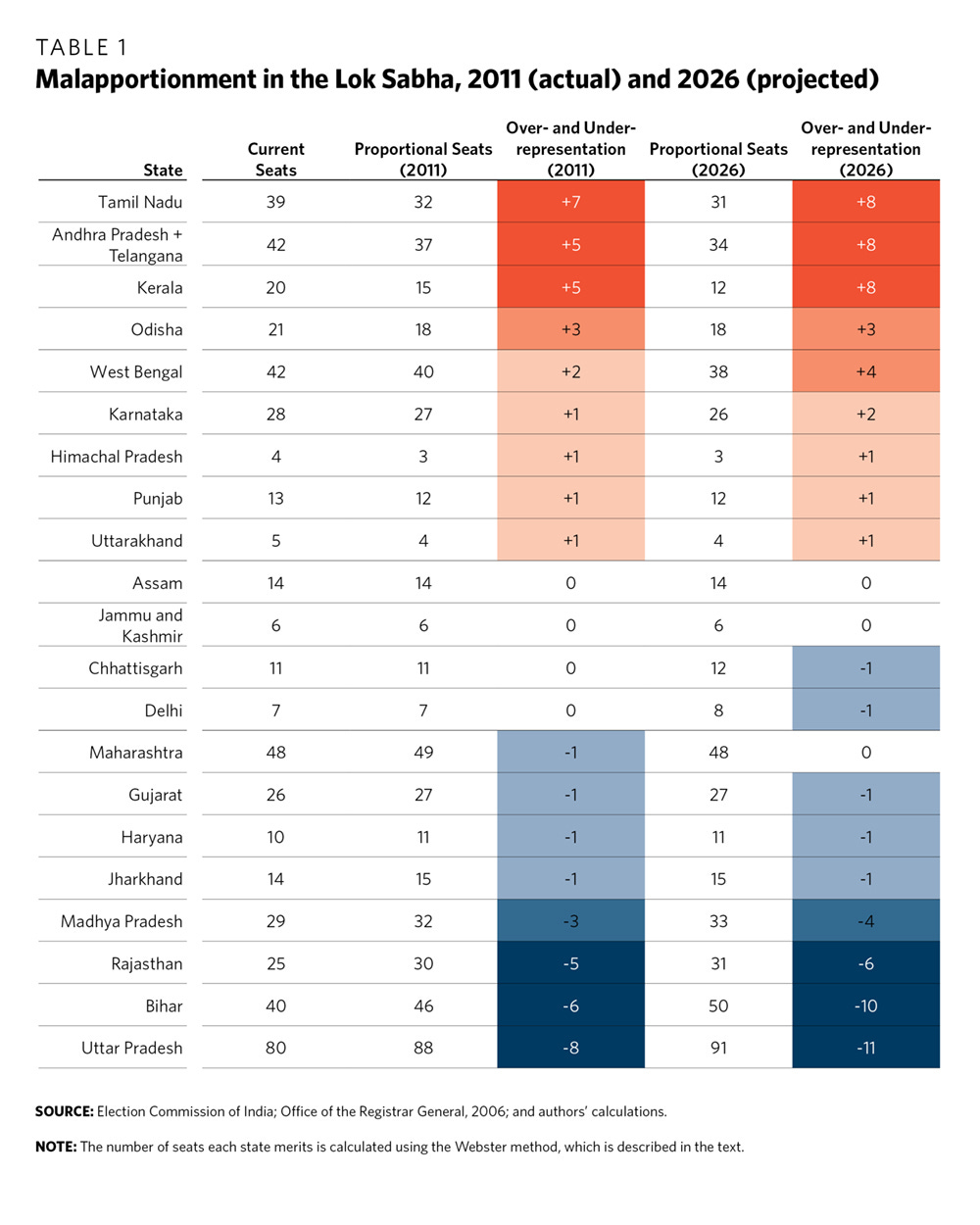

This table, from an analysis by Vaishnav and Hintson in 2019 shows you just how much things would change.

Based on 2011 census numbers, “four north Indian states (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh) would collectively gain 22 seats, while four southern states (Andhra Pradesh, Kerala, Telangana, and Tamil Nadu) would lose 17 seats”, the analysis concluded. “Based on our population projections, these trends will only intensify as time goes on. In 2026, for instance, Bihar and Uttar Pradesh alone stand to gain 21 seats while Kerala and Tamil Nadu would forfeit as many as 16.”

As we saw in the debate over how the 15th Finance Commission ought to distribute taxes, South Indian states will vigorously fight efforts to undercut their political or economic power simply because their fertility rates came down over the last 50 years.

At the same time, even if it reflects a failure of their governments on an official policy objective, should citizens in North Indian states be penalised, politically and economically, because their population growth remained high?

Instead of taking away seats from some states and giving them to others to solve the problem, academically called “malapportionment”, one of the proposed solutions has been to simply follow what was done in the 1950s and 1960s and increase the total number of seats, giving more to the states with larger populations.

Fuller House

This would still lead to a major change in power within the Lok Sabha, since North Indian states will have many more seats than before, but at least no state would have to lose representatives. It would need a Constitutional Amendment, since there is a 550-seat upper-limit at the moment, but that might be an easier task to achieve than taking away seats from a state.

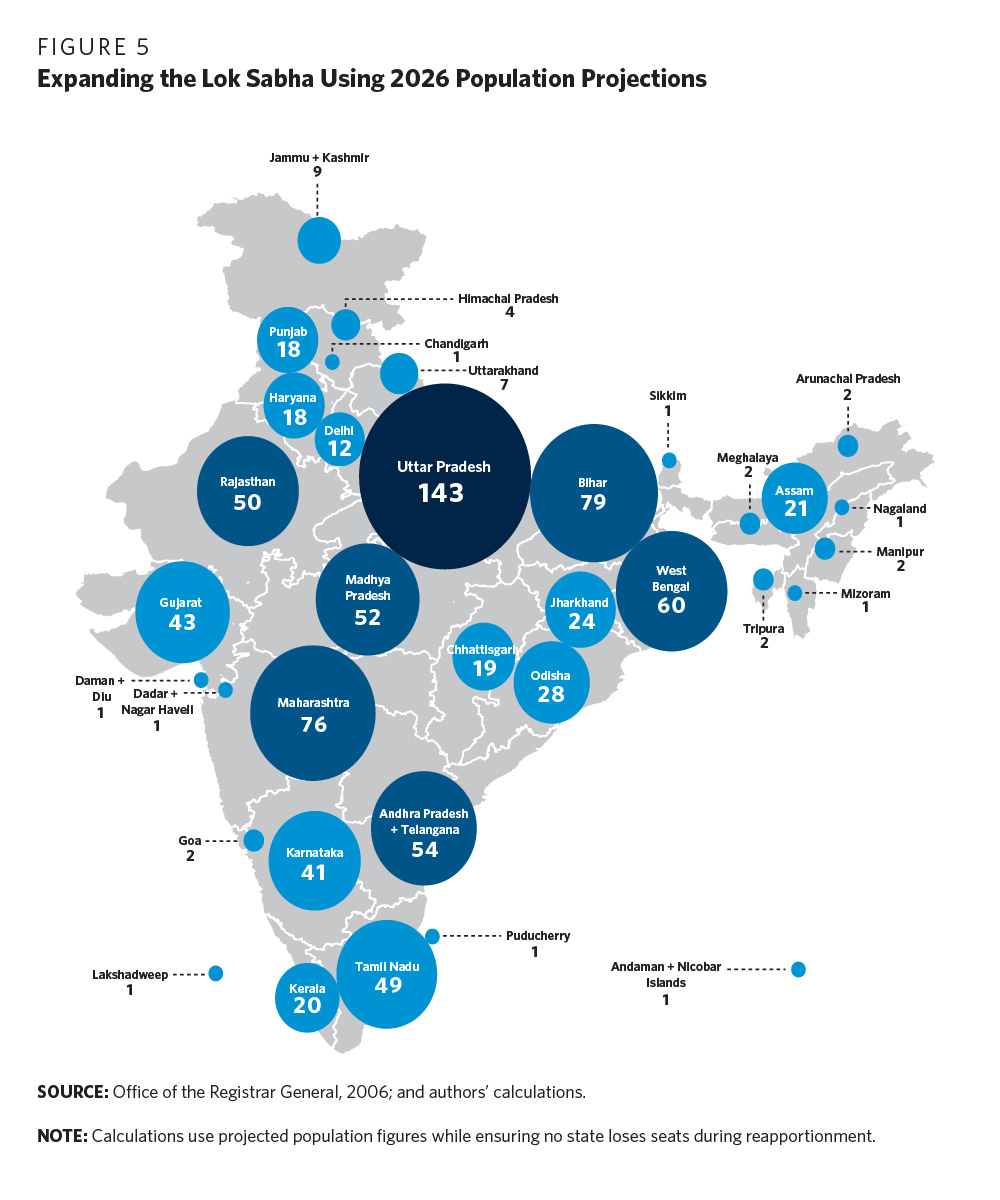

Vaishnav and Hintson put together a map of what this might look like, taking projected population figures in 2026 as the basis:

The result: A Lok Sabha of 848 seats, not far from the 888 that the new Parliament building is making space for.

Narendra Modi’s large Parliamentary majorities have given him the foundation to alter the shape of the Indian Union – as with the unilateral stripping of autonomy of Jammu and Kashmir in 2019, or the introduction of the Goods and Services Tax before that – in ways that previous prime ministers were unwilling or unable to.

But his centralising tendencies and tendency to bulldoze policies, as we have noted over and over again on this newsletter, will make states especially in the South deeply suspicious of any effort to alter their position within the Indian Union.

Of course, the 2026 changes would come after the next Parliamentary elections, but if anything the BJP has made it clear how it is willing to embark on projects that are decades in the making. With the likelihood – as reflected by the new Parliament building – that Modi and the BJP plan to eventually follow through on the redistribution of seats and the understanding that the delimitation question cannot be put off forever, it is imperative that a public dialogue about how best to resolve this matter begin in earnerst.

Or else it may play out just as demonetisation or Article 370 did, with a party with majority at the Centre taking a massively significant move without consultation with either the Opposition or the public at large.

As economist Ajit Ranade has argued:

“We may desire “equality” of constituencies, but economic development and demographic patterns do not develop uniformly across the country. Some states have achieved zero population growth while others still have very high fertility rates. This pattern too has a north-south dimension. It is as if the economic centre of gravity is shifting south and the political centre of gravity is shifting north…

It is not too early to begin addressing the issue of delimitation at the national level… Just as the nation took more than 12 years to come to a consensus on “one nation one tax” (i.e. the roll-out of the goods and services tax), a national consensus exercise should be started to sort out issues much before 2026.”

Read also:

The delimitation question was one of the reasons I wrote at the start of the year that the the states vs Centre battle will dominate India over the next decade.

We’ve also discussed issues of federalism, centralisation and more on several Friday Q&As:

Louise Tillin on a “defining moment” for the future of Indian federalism.

Neelanjan Sircar on Narendra Modi’s politics of vishwas.

“No matter how centralising Modi is, he will need states’: Yamini Aiyar on federalism after 2014.

Flotsam and Jetsam

Is it time for you to give up on India? In a much-read essay,Bloomberg’s Andy Mukherjee admitted that he is losing hope in the country because of a disturbing arbitrariness in governance, the return of the “defeatist slogan of self-reliance” and the inept authoritarianism under Modi. V Anantha Nageswaran, a member of the Prime Minister’s Economic Advisory Council, thought Mukherjee was wrong.

The ruling Telangana Rashtra Samithi won 55 out of 149 wards in the Greater Hyderabad Municipal Council elections, just barely ahead of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s 48, and the All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen’s 44, an indication of the BJP’s intentions of becoming the principal opposition in the state.

West Bengal, Delhi and Jharkhand have chosen not to sign on to the Centre’s rental housing scheme aimed at bringing migrants back to the cities.

India summoned the Canadian High Commissioner to complain after Prime Minister Justin Trudeau spoke in support of the protesting farmers. The External Affairs Ministry said Trudeau’s “comments have encouraged gatherings of extremist activities in front of our High Commission and Consulates in Canada”.

After years of dithering, Tamil actor Rajinikanth announced that he would launch a new political party in 2021, that would promise to bring “spiritual politics” to the state where elections are due next year.

Pfizer has requested emergency authorisation to use its Covid-19 vaccine in India. Meanwhile, the manufacturers of Covaxin, an indigenous vaccine still undergoing trials, had to clarify that Haryana Health Minister Anil Vij – who tested positive for the virus after publicly taking a test dose – had only received the first of two doses, with immunity only likely to develop two weeks after both injections.

Can’t make this up

A 12-member team with no support from the Indian Chess Federation won India’s first-ever gold medal in the FIDE Online Chess Olympiad, earning praises and congratulations from all around including the Prime Minister.

When the medals actually arrived in India, though, the team was asked to pay customs duty on them. Customs officials “had opened up the package and asked me what was inside, and what it was made of”, the team’s vice captain said. “I had to give them an official document on the chemical composition.”

Thanks for reading the Political Fix. We’ll be back on Friday with a Q&A and links. Send feedback to rohan@scroll.in.