The Political Fix: What unites protesting farmers and critics of RBI’s corporate banks proposal?

Fears of big business and a concentration of power.

Welcome to The Political Fix by Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, a newsletter on Indian politics and policy. To get it in your inbox every week, sign up here.

We don’t charge for this newsletter, but if you would like to support us consider contributing to the Scroll Reporting Fund or, if you’re not in India, subscribing to Scroll+.

The Big Story: ‘Conglomerate capitalism’

For most of the last few months, Delhi has managed to ignore the large-scale agitation happening next door in Punjab. Sure, there was the headache of figuring out how to send coal supplies and military equipment to the armed forces at the border because the agitation had resulted in a halt in rail traffic in the state. But by and large, the farmer protests were treated as a sideshow – with top Bharatiya Janata Party leaders turning their focus instead to a municipal election in Hyderabad.

The farmers were up in arms because of three laws passed in chaotic fashion by Parliament in September, which we wrote about at the time. The laws, which broadly make it possible for farmers to sell their produce outside of government-run mandis and create the conditions for contract farming, were hailed as the “1991 moment” for Indian agriculture.

But the very people whom the laws were supposed to “liberate” did not see them that way, especially in Punjab. Though there was initially pushback from agriculturalists around the country, the anger in Punjab – which ended a decades-long alliance between the Shiromani Akali Dal and the BJP – only seemed to grow. Yet Delhi was dismissive, with delegates from the protesters being received only by bureaucrats.

So the farmers decided to get Delhi to listen to them.

Despite a remarkable show of force from authorities in Delhi and neighbouring Harayana to stop peaceful protesters – deploying thousands of security personnel, huge roadblocks, barbed wire, water cannons in the North Indian winter, tear gas shells, digging a giant ditch on a national highway and effecting midnight raids to arrest protest leaders – the farmers managed to reach the border of the national capital.

Along the way, they also made headlines by offering water and food to the very security forces trying to keep them out of Delhi and managing to turn off a water cannon during the protest, They also prompted a political squabble between the Punjab chief minister and the chief minister of Haryana – who tried to prevent them from traveling through his state, despite support from within.

The impact was clear when it was ultimately Amit Shah, the Union Home Minister, who was trotted out to say that the government is “ready to deliberate on every problem”. But he laid down a condition. The protesting farmers should be willing to be shunted off to a stadium in Burari, far from the political centre in New Delhi.

Meanwhile, the BJP’s infamous IT cell got to work, throwing muck at the protesters by insisting they are secretly Muslims, supporters of the secessionist Khalistani movement – and therefore evil – or just “middlemen” and not real farmers. This tactic might work for the national audience but, as Shekhar Gupta points out, it won’t get much traction in Punjab, the one North Indian state that has consistently rejected the Narendra Modi-era BJP.

Over the weekend, the farmers said “thanks, but no thanks” to Amit Shah, and decided to hunker down on the Delhi border as support from fellow agriculturalists in Haryana and other surrounding states continued to grow.

We’ve written in the past about why these farmers are protesting – read also Sukhpal Singh, Varinder Bhatia and Sunilam on this.

Chief among the farmers’ concerns is the fear that dismantling the state government-led mandi system and allowing contract farming will permit large corporations to control agriculture, ultimately taking away any limited political and pricing power that this constituency had. The Shiromani Akali Dal’s Harsimrat Kaur Badal even brought up Reliance when she resigned from Modi’s cabinet.

Concentration of power

Far away from the cold winter streets of the Delhi border, howls of protest were echoing about a different issue that had nevertheless provoked by a similar anxiety.

An Internal Working Group set up by the Reserve Bank of India last week suddenly recommended that the banking sector should to be opened up to large corporations and big business. The group’s recommendation came even though all experts but one that it spoke to were against the idea. This provoked immediate outrage.

“Dangerous”, said former Finance Minister P Chidamabarm. “Risky proposition” was the conclusion from S&P Global Ratings. Former RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan and former deputy RBI governor Viral Acharya called it a “bombshell” that would “increase the importance of money power yet more in our politics, and make us more likely to succumb to authoritarian cronyism”.

As with the farmers, the principal fear is a further concentration of power that undermines other players, in this case referring to other businesses that don’t have access to “connected lending”, the regulators and the government itself.

As former Chief Economic Advisers Arvind Subramanian and Shankar Acharya and former Finance Secretary Vijay Kelkar put it:

“The Indian economy already suffers from over-concentration. We not only have concentration within industries, but in some cases the dominance of a few industrial houses spans multiple sectors…

Indian capitalism has long been stigmatised because of the murky two-way relationship between the state and industrial capital. If the line between industrial and financial capital is erased, this stigma will only become worse.

Corporate houses that are already big will be enabled to become even bigger by having access to raise and redirect resources, allowing them to dominate the economic and political landscape. A rules-based, well-regulated market economy, as well as democracy itself — already shaky and ravaged by broader trends in India and also internationally — will be undermined, perhaps critically.”

Not everyone is as set against the proposal. Ila Patnaik and Radhika Pandey point to the massive regulatory failures in the financial sector, saying that any move would need the government to majorly shore up its capacity on this front.

Suyash Rai goes a step further, saying that there is a good reason that the RBI is considering this move right now. In an emerging economy where capital is scarce, a second-best option – he suggests a “build-operate-dilute” model – might be necessary. However, the authorities will have to work hard to mitigate the power that industrial houses will acquire.

Modinomics

Concentration of power is, in fact, one of the central features of the Modi era, not just politically as we have covered in our various articles on federalism and centralisation, but also in the economic sphere.

It is one the main subjects of a recent insightful issue of Seminar, edited by Rohit Chandra and Rahul Verma. Harish Damodaran writing in the issue, calls it a shift from the ‘entrepreneurial capitalism’ of the 1990s and early 2000s to a “conglomerate capitalism”:

“What has been remarkable about the economic and political stability distinguishing the Modi regime is its also presiding over a manifest decline of Indian capitalist enterprise. Out of the top 200 listed Indian promoter-run companies ranked by total revenues in 2014-’15, about 57 have since gone bust, been hauled to the National Company Law Tribunal by lenders or undergone management change…

Across many sectors today – telecom, airlines, steel, cement, aluminium, synthetic fibres, polymers, paints, cars, trucks, two-wheelers, tractors, tyres, consumer electronics and electricals, toiletries, tea and biscuits – there are two, at most three, players commanding more than 50% market share. What’s more, some groups have market leadership that straddle multiple industries…

The trend of industrial consolidation – more and more sectors being taken over by fewer and bigger entities – has been greatly facilitated by demonetization and GST that have eroded the competitive advantage smaller firms hitherto had from dealing in cash and not paying full taxes.”

Damodaran even poses a question that we will undoubtedly return to, as part of attempting to understand how India’s political and economic space has been changed under Modi.

“To what extent was the phase of ‘entrepreneurial capitalism’, which also witnessed very high churn with more new players coming in than the ones dropping out, connected with the rise of regional parties and the era of coalition governments? Could the absence of a strong Centre have, in fact, been conducive to a capitalism that was fairly dynamic and entrepreneurial?”

For now, anxieties about a few big businesses dominating India – which also includes the BJP’s corporate-friendly anonymous electoral bond mechanism for political funding – are being aired, both on the streets and in the pink papers.

Even if they plow ahead with their agenda, in agriculture and banking, will the thinkers and policymakers of the Modi government acknowledge these concerns and how they intend to address them?

Flotsam and Jetsam

The BJP’s Himanta Biswa Sarma said that the Citizenship Act amendments and the National Register of Citizens are no longer part of the discourse in Assam, where elections take place next year.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi suddenly resurrected the idea of simultaneous elections, a concept he had majorly pushed in his first term, despite the many questions about how it would actually work and whether it would be good for the country, since it is likely to have a further centralising effect.

There is talk of postponing or canceling the winter session of Parliament, which would normally have dates by now, because of the continuing Covid-19 pandemic. Doing so, however, would impact the tabling of the all-important Fifteenth Finance Commission report that would give visibilty to the states on their access to funds over the next five years.

Gross Domestic Product growth numbers for the second quarter of the financial year were surprisingly better than expected, only a contraction of 7.5%, though there are fears that this may have been because of a “massive purge in costs such as employee cost by corporates and businesses, which could turn a potential headwind in future”, according to analysts at the State Bank of India.

The BJP has turned out in force for municipal elections in Hyderabad, sending Home Minister Amit Shah, BJP President JP Nadda and UP Chief Minister Adityanath among others to campaign for some very local polls, sending a message about the party’s intentions in Telangana.

The first phase of District Development Council elections in the Union Territory of Jammu and Kashmir saw 51% turnout. Results will be out on December 22.

External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar and National Security Advisor Ajit Doval made visits to Nepal and Sri Lanka respectively over the last week, in efforts aimed at countering growing Chinese engagement with India’s South Asian neighbours.

Can’t make this up

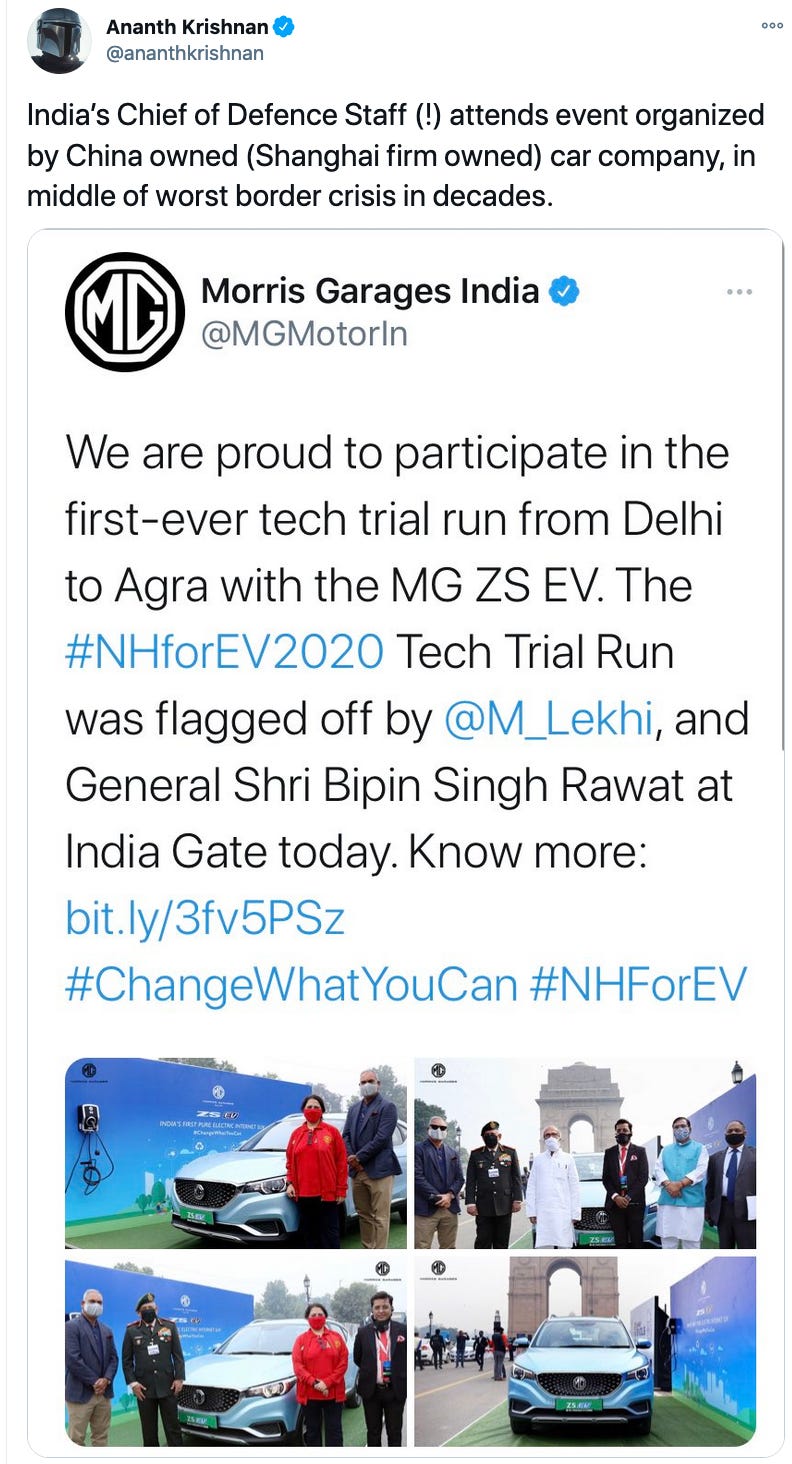

There’s no much to add to this, other than the question posed Suhasini Haidar, “Why is our Chief of Defence at any car company event at all?”

Thanks for reading the Political Fix. We’ll be back on Friday with a Q&A and links. Send feedback to rohan@scroll.in.