The Political Fix: What the Taliban’s sudden success means for India – and Indian politics

A newsletter on politics and policy from Scroll.in

Welcome to The Political Fix by Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, a newsletter on Indian politics and policy. To get it in your inbox every week, sign up here.

Our small team wants to cover the big issues. That is why we are appealing for contributions to our Ground Reporting Fund. If you’d like to assist our effort, click here.

The Big Story: Af-Pak is back

No words can sugarcoat the bitter taste for India that comes with Kabul, and most Afghanistan, reverting to Taliban control after two decades of American military intervention.

Afghanistan shares only a notional border with India – on paper, the countries have a 106-kilometer boundary, though that lies in Pakistan-occupied territory. But what happens in South Asia has major ramifications for Indian interests and ambitions in the region. Still, there may be a rather perverse silver lining for the Bharatiya Janata Party.

Here’s what the Taliban takeover means for New Delhi.

Immediate concerns

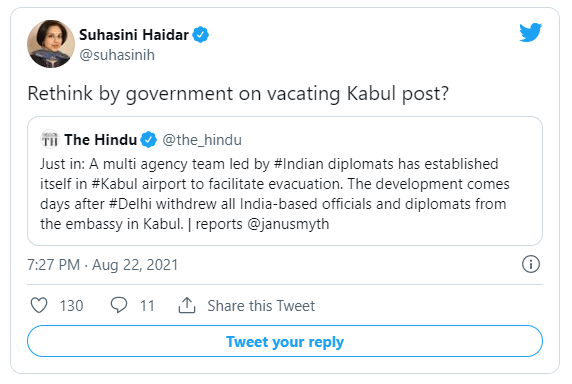

The Indian ambassador along with most of the embassy staff was evacuated from Afghanistan a week ago, given the rapidly deteriorating security situation in the country. But the job for the Indian team did not end then, given the number of citizens still in the country, as well as Afghans who New Delhi is choosing to help evacuate.

On Sunday alone, according to the Hindustan Times, India evacuated 540 people, including 475 Indian citizens. Some returned directly from Kabul and others via Tajikistan and Qatar. Some of these operations have been complicated. This is primarily because of the situation outside the Kabul airport, where those seeking to leave have run into potentially dangerous situations at Taliban check posts.

On Saturday, for example, there was confusion for a few hours after Afghan media reported that 150 Indian citizens had been “abducted” by the Taliban, which denied the claims. Later it emerged that the Indians were safe. But Afghan citizens – including Hindus and Sikhs hoping to be evacuated to India – had to return after the Taliban refused to let them leave the country.

Efforts are still on to bring back the remaining Indian citizens, as well as Afghans to whom New Delhi has decided to extend support. It is likely that the questions of how to politically and strategically deal with the Taliban government will – at least in public – have to wait until after evacuation operations have been completed.

Strategic implications

An unusual request emerged from the Taliban last week, as India began preparations to evacuate its embassy. As Rezaul H Laskar reported,

“Senior Taliban leader Sher Mohammed Abbas Stanekzai reached out to the Indian side with a surprise request: Would India retain its diplomatic presence in Afghanistan?

The request was conveyed informally and indirectly by the Taliban leader, who is part of the leadership of the group’s political office at Doha in Qatar...

The message took Indian officials in New Delhi and Kabul by surprise, people familiar with developments said on condition of anonymity.”

Stanekzai, who was known as “Sheru” when he trained at the Indian Military Academy decades ago, did not only suggest that Indian diplomats would be kept safe. He also specifically conveyed the message that the checkposts in Kabul were being maintained by the Taliban and not by Pakistan-based terror groups like Lashkar-e-Taiba that would have targeted Indians.

This sort of outreach is among the reasons why the 2021 evacuation of the Indian embassy and its citizens is taking places in circumstances quite different to similar efforts in the past, such as in 1993 when a security officer was killed.

One of the key differences is the way the rest of the world is reacting. In the 1990s, Taliban-controlled Afghanistan was treated as a rogue state by nearly all the major powers. But their current success comes after several years of Western nations seeking to provide legitimacy to a group that the US still designates as a terror outfit – primarily to construct a narrative that would explain the withdrawal of their forces.

Besides, China, Russia and Iran have all made it clear that they intend to work with the Taliban to secure their own interests in the region. This gives the group political cover beyond the support, funding and training it has always received from Pakistan.

This is the changed environment that New Delhi confronts, and it is one in which it will have to tread carefully. Stanikzai’s request, for example, was eventually denied after India decided that the Taliban assurances of security could not be taken at face value.

India will face similar questions about its engagement with Afghanistan over the next few years. New Delhi poured billions of dollars into the country over the last few years, funding development and humanitarian projects, while also providing training and education to Afghans in India and expanding its trade relations.

Will India put a complete halt to these efforts now that the Taliban are in charge? There have been murmurs that Kabul’s new leaders want India to continuing pouring money into the country. But New Delhi will be deeply sceptical of any promises – given Pakistan’s intentions for the group.

At the political level too, India will have to calibrate its plans. New Delhi has long been reluctant to engage with the Taliban, a debate that we discussed in our interview with Avinash Paliwal back in May. Back in the 1990s, it decided not to officially engage at all – a policy that many saw as responsible for making the infamous Indian Airlines hijacking case in 1999 even harder to handle.

Many now believe that India’s last-ditch efforts over the last six months to open lines to the Taliban may have been too little, too late. Former diplomat Vivek Katju writes,

“The visual manifestation of Pakistan’s current centrality was manifested, above all, in the visual images of Pakistan foreign minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi welcoming a delegation of leaders of the erstwhile Northern Alliance at the Pakistan foreign ministry in Islamabad on August 16.

For me, these images were far more telling of Pakistan’s success than those of the Taliban in the palace complex of Kabul or occupying the speaker’s chair in the Indian-built Parliament building in Kabul...

All these leaders have harboured deep reservations, even anger, against Pakistan. It would not have been easy for them to go to Islamabad to seek its intervention to get the Taliban to conduct itself responsibly in its hour of victory. And they are all doubtless fully knowledgeable about Pakistan’s enormous role in the Taliban’s success. That they have gone to Pakistan and not come to India has a clear message. They are aware that India can now simply play no role at all in the unfolding of events in Afghanistan.”

That said, the US withdrawal may accelerate the breakdown of ties between Washington, DC and Islamabad – remember, US President Joe Biden still has not spoken on the phone to Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan.

C Raja Mohan explains:

“The withdrawal of all US troops from Afghanistan is likely to accelerate current trends in India’s relations with the United States, China, and Russia: greater cooperation with Washington, deeper conflicts with Beijing, and wider fissures in the traditional strategic partnership with Moscow. Reinforcing these structural shifts—and their mirror image—are Pakistan’s changing relations with the United States, China, and Russia...

It was widely assumed that India’s strategy of multi-alignment—sustaining simultaneous strategic partnerships with the United States, Russia, and China—would survive major regional and global changes. But the growing security challenges from China have rendered that assumption moot and nudged India closer than ever before to the United States. The latest developments in Afghanistan could intensify Sino-Indian contradictions, consolidate Indian-U.S. relations, and produce greater distance between India and Russia—quickening the pace of the transformation of India’s great-power relationships that was already underway.”

Domestic politics

Across Indian Twitter, every faction has sought to interpret the Taliban takeover through the lens of their own domestic political lense. This sometimes led to odd context-less comparisons, as with the commentary about the Taliban leadership’s decision to hold a press conference.

A number of local politicians too have picked up on this trend. Samajwadi Party MP Shafiqur Rehman Barq, for example, compared the Taliban victory to Indian independence movement. He said it was a personal matter for the Afghans – leading to a sedition case against him.

Meanwhile, the Bharatiya Janata Party has embraced Taliban-controlled Afghanistan as the latest foil against which to compare Narendra Modi’s India. The party has used it as a dogwhistle against Indian Muslims who complain about economic conditions at home and a weapon to be deployed in domestic political debates.

Ramratan Payal, a BJP leader from Madhya Pradesh, responded to a question about high fuel prices in India by telling the journalist asking to “go to Afghanistan”.

Meanwhile, BJP President JP Nadda and Union MInister Hardeep Singh Puri misleadingly connected the current developments to the government’s controversial Citizenship Act amendments, passed in 2019 but still not yet notified today.

The laws controversially sought to give an accelerated citizenship pathway to undocumented migrants from three neighbouring countries, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Bangladesh – but only if they are not Muslim. The party then connected this to a proposed National Register of Citizens, essentially suggesting that millions of Indian Muslims might be forced to prove their citizenship, even as undocumented migrants of other religions would face no such scrutiny.

The BJP never offered a clear explanation for why secular India would be adding a religious test to its citizenship laws, or why it only picked Muslim-majority neighbouring countries and not all of those with which it shares a border or colonial history.

Importantly, the Citizenship Act amendments have a cut-off date of 2014, meaning no minorities in Afghanistan today would be covered under the law – an important bit of information that Nadda and Puri have conveniently ignored.

Still, comments like this and other concerns about a “Taliban mentality” are likely to continue featuring as a Muslim dogwhistle in Uttar Pradesh election campaigning over the next year.

Linking Out

Manas Chakravarty has a brilliant send-up of the poetic tone that the Reserve Bank of India has been taking in its recent reports.

“In some respects, the BJP has now become a victim of the astonishing pace of its ideological triumphs in this dominant phase,” writes Asim Ali, explaining how the calls for population control and the Uniform Civil Code could backfire.

Satish Deshpande and Valerian Rodrigues speak to KV Aditya Bharadwaj about whether India needs a caste census and what the implications of such an exercise would be.

Can’t make this up

The never-ending meme train that is the Subcontinental TV drama:

Thank you for reading the Political Fix. Send feedback to rohan@scroll.in.

Support our journalism by contributing toScroll Ground Reporting Fund. We welcome your comments atletters@scroll.in.