Saturday Q&A: Avinash Paliwal on the challenges posed to India by the Taliban and Myanmar’s military coup

Plus, is India over-relying on Sheikh Hasina?

Welcome to The Political Fix by Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, a newsletter on Indian politics and policy. To get it in your inbox every week, sign up here. All The Political Fix Q&As are collected here.

India’s second Covid-19 wave is a huge story. Help our small team cover the big issues. Contribute to the Scroll Reporting Fund.

Note: We’ve been focusing on the pieces over the last few weeks, because of how much there is to say, but if you’ve been missing the links and want them back, please let me know. Write to rohan@scroll.in

Even as it struggles to handle the brutal second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic, India also faces the prospect of a deeply unsettled neighbourhood. In Afghanistan, the impending withdrawal of US troops by September all but ensures some degree of violence and a bigger role for the Taliban, with Pakistan’s support. In Myanmar, the military junta’s coup has added to pre-existing tensions, with the country at risk of descending into civil war.

Avinash Paliwal is senior lecturer in international relations and deputy director of the SOAS South Asia Institute, as well as the author of My Enemy’s Enemy: India in Afghanistan from the Soviet invasion to the US withdrawal, published in 2017.

Paliwal’s work has focused on using foreign policy analysis tools to better understand India’s decision-making processes when it comes to immediate neighbours. In My Enemy’s Enemy, for example, he tells the story of India’s Afghanistan policy over the last few decades through the lens of bureaucrats and politicians who largely either see the country as the staging ground of a proxy battle with Pakistan, or as a neighbour that could serve New Delhi’s long-term interests. He is currently researching India’s foreign policymaking processes towards Myanmar and Bangladesh.

I spoke to Paliwal about the last time India had to deal with an ascendant Taliban, what New Delhi is getting wrong in its approach to Sheikh Hasina and the military junta in Myanmar, and why he thinks that the current External Affairs Minister is not acting on impulses that are evident within the diplomatic corps.

Could you tell the readers a little bit about your background?

I did my PhD from King’s College London, finished it in 2015. Since 2017, I have been in lectureship and now senior lectureship positions. In terms of my research, my focus has fundamentally been on South Asian strategic affairs with emphasis on foreign and security policy making processes.

In terms of the specific themes, I have focused initially on the making of India’s Afghanistan policy, since the Soviet invasion in 1979 till 2016, when I wrote my first book [My Enemy’s Enemy: India in Afghanistan from the Soviet invasion to the US withdrawal]. Right now, I’m working on a project which offers a strategic history of India’s immediate east.

When I use the term immediate east or near east from an Indian perspective, it is to cover Bangladesh and Myanmar in particular. How, since 1947, since post-independence, has India behaved towards these two neighbours and how does it balance the sometimes competing requirements between these two. But also India’s own economic and strategic interests in the wider east as well as the sense of competition that has dawned on India’s foreign policymaking as far as the Chinese influence is concerned, including in North East India.

Did you always want to focus on this as part of your research?

The reason I got interested in India’s neighbours primarily was because of my fascination with conflict and polarisation in India itself. My first foray as a student into Indian foreign and security issues was looking at the Kashmir dispute during my graduate studies. And as I proceeded in my career, I got both lured by and convinced of the need to unpack in detail the finer empirical details of India’s behaviour in its region.

The reason I continued in a professional setting, a bit more emotionally detached but professionally committed to remain in India’s region, was less on the advice of my peers and my advisors, more by the fact that I found that there is simply not much work done. There was a lot of mismatch, at least till about five to six years ago, on the data and analysis that was existing on India’s behavior in its immediate region, and the wider narratives of Indian foreign policy in a global sense.

This is where I really thought that there is an empirical, theoretical or conceptual bridge that needs to be built, wherein we are able to actually better understand how India performs in its region to be able to gauge its performance at a global level and its true potential.

Did you take any particular lens to your research?

Yes, when I started the India-Afghanistan project, there was a competing intellectual dynamic at play. On one hand, I wanted to step away from bilaterals, which have dominated India’s policy scene, and which do not always offer a comprehensive picture of India’s international thought and practice. But at the same time I wanted to use those bilateral frameworks, because India has been so invested in bilaterals historically, to tell a wider global story and also be able to analyse the intricacies of India’s foreign policy.

I relied on foreign policy analysis frameworks, a sub-discipline within international relations.

I wanted to get away from the larger canons of international relations – realism, liberalism, constructivism – to actually look at the mechanics of policymaking. Within foreign policy analysis as a field, I zeroed in on a framework called the advocacy-coalition framework.

Advocacy coalition framework allowed me to give some analytical coherence to the otherwise messy policymaking processes that we often witness in India.

There are partisans – those policymakers across bureaucratic and political lines who would be more averse to dealing with anyone in Afghanistan who had any sort of relationship with Pakistan.

And there are conciliators, who would be more open – not in an ideological or political sense, butu in an operational sense – to dealing with those figures in Afghanistan, including the Taliban, which rely on links with the Pakistani security establishment.

That framework helped give some degree of analytical coherence and helped me make sense of the processes of decision making that happened in India.

For those not too familiar, are there other spaces where these frameworks have been used?

The framework is widely used. But, there is a tilt in favour of countries which are relatively more developed. I’m reluctant to use the term West, because it’s quite a catchphrase for very diverse societies and ideas.

But the empirical cases used to develop the field, including these frameworks, came from counties like the United States and Europe, which have a very formalised, if not formulaic, way of making policy decisions.

In the case of India, these are conceptual frames that have been under-utilised. But they can be utilised very fruitfully from an analytical sense, and the discipline can develop much more by using or drawing upon the experience of India.

Have you seen it be used in other non-Western contexts?

Not just advocacy coalition framework, but other foreign policy analysis models such as bureaucratic politics, organisational culture, psychological contexts – there has been a focus on policymaking in Turkey, in South Africa, even certain Middle Eastern countries. But these are limited cases.

They cannot compare in terms of quantity or quality of analysis to those looking at US foreign policy or Britain’s policymaking processes.

Having said that, within the field, there is a movement and a strong commitment to decolonisation, and to figure out the global sources of international relations as a discipline itself. This was not a discipline forged in the West. This was a discipline that came to be dominated by Western narratives and experiences.

And there is a movement to dig out those histories, wherein non-Western experiences were equally pivotal in informing the development of this discipline, but over the period of time got subdued or overshadowed by voices which were not from non-Western contexts.

Anything in particular you’d want to point the readers to?

One person whose work comes to mind right now, is Dr Martin Bayly, at the London School of Economics. He recently wrote a piece about multiple sources of India’s international thought and practice. At least in the Indian context, Martin has done excellent work to show how, even before the First World War, there were thinkers from India who would try to write about these histories and inform debates in a meaningful way.

There was a whole generation of thinkers who influenced Western thought about international relations as well, which is often missed. Even scholars like Rahul Sagar, who have been working on histories of Indian international relations thought, throw a lot of important light on India influencing the rise of the discipline itself, if not its contemporary make.

On to Afghanistan. In your framework, we have partisans, who see involvement in Afghanistan as a way to take on Pakistan and choose whom to engage with – or not to talk to – in that context, and conciliators, who believe India needs talk to all of the players including the Taliban. Where are we placed as we move towards an American withdrawal this year?

The debate is very acute right now within India’s foreign policy corridors as to which direction to tilt. At least till two years ago, I would say that the partisan narrative continued to dominate, simply because there was no pressing need to accommodate the Taliban, because there was no clarity about which side the US itself would take.

Over the last two to three years, American decision making has become very clear, now that the withdrawal is actually taking place. I think the debate has become more urgent and not just acute.

[There is] the conciliatory narrative – not in a political or ideological sense, not one that seeks to justify or endorse the Taliban – but one that says we cannot overlook the realities on the ground of increasing Taliban prominence both militarily and perhaps even politically within Afghanistan.

There [are those] within the Ministry of External Affairs, within India’s intelligence services, within section of the Armed Forces and the bureaucracy, and even those units which are not part of the government but actively promoting India’s interests in Afghanistan, [pushing] to actually adopt that approach.

This has not happened, despite very clear signals from some important influences within the government of India’s Afghanistan policy in tilting the balance against the partisan narrative at a political and official level.

The policy continues to betray a sense of partisanship, even though there is increasing salience of the conciliatory narrative within India at the moment.

In the book you argue that the existence of both partisans and conciliators may be what makes India’s ties with Afghanistan somewhat robust, because it has been able to go back and forth between these groups. But there is also danger in the ‘wrong’ set being in power at the wrong moment?

It would be difficult for India either which way, given the situation in Afghanistan right now. Just because there are voices advocating conciliation does not mean the Taliban would actually deliver in securing India’s core interests, even if it comes to power. But one thing that is also very sure, to continue on the partisan line will not help India in expanding its base of influence and access across different power holders in Afghanistan in a post-Ghani, post-US scenario.

In both circumstances, India will have to take tough decisions. And there will be temporary setbacks in India’s visible presence, forget even influence, for the time being. But the question is, which of these two routes can actually ensure that India weathers the storm and continues to retain in the medium-term its presence and secure its interests.

There is merit to the conciliatory narrative at the moment, simply because the kind of military presence that the Taliban has and the political strategy it is adopting, means that this narrative of the Taliban being a fragmented force, that you can exploit fissures from within, will not pan out in the immediate future, even if may happen later on when the pressures of governance itself weigh them down.

Right now, there is a very clear indication that the Taliban will hold power in some way or the other in Kabul in the coming months. And that means, there is a need for India to recognise that.

How would you compare the situation to the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, and then the Taliban takeover in the mid 1990s?

I would be reluctant to compare the 1990s with the 2020s. Because, despite certain similarities of characters and dynamics – a weak centre and fragmented governance and power – there is a very clear sense among the various parties, including the Taliban, that they cannot afford to go back to the 1990s moment.

The trauma of that fragmentation did not just affect neighbours, it affected the people of Afghanistan themselves. So what we’re seeing is that, whichever party comes to power, there would be a clear sense of having some degree of whatever kind of stability they can get, ugly or not.

Perhaps that is why there are figures within the Afghan government who are much more willing to talk with the Taliban today than they are even with their own sitting president, Afghan Ghani.

So there are structural similarities, but personalities are different.

The key ally India had in the late 1980s and 1990s, President Najibullah, was in a different structural context. He had much more acceptability among sections of the Pashtun community and also the non-Pashtuns. He had political commitment to a nationalist Afghan cause.

If you have to compare, I think former President Hamid Karzai might have come close to being in that position.

India’s support for President Ghani over the last few years, has been more complex than with Najibullah. And partly, that’s why I think India has in recent months diversified or consolidated its relations with other power brokers within the mainstream body politic.

Look at the visits that have been happening: [former Chief Executive of the Afghan government] Abdullah Abdullah, [former Northern Alliance commander] Ismail Khan, [former deputy to the chief executive] Muhammad Mohaqiq, even [former Afghan Vice President Abdul Rashid] Dostum – all these various figures who are very seasoned power brokers, known as warlords from the 1990s era, India has doubled down in supporting them over the past few months.

Because it is not clear to India that, even if it reaches out to the Taliban – and my understanding is that there have been silent outreaches over the past few years – they are not sure the Taliban will be able to deliver.

This is where the complication for the conciliatory narrative comes in. You want to talk to them, but are they interested in talking to you?

For the reader who is not so familiar, how did India deal with the Taliban question in the 1990s when they were in power?

There was a near total breakdown of any communication between India and the Taliban, even at an intelligence level. India did not have an embassy between September 1996 and October 2001. India did not recognise the Taliban government. India was both officially and covertly committed to the so-called Northern Alliance. It had not invested in talking to the Taliban.

The lack of outreach was most pressingly felt during the 1999 Kandahar hijacking. This had a very interesting effect on India’s policy learning curve with Afghanistan. They realised that, while the hijacking negotiations were going on, their allies in the Northern Alliance were not able to help them at all.

This was because of the fractured nature of the Afghan state at the time, but also there was a lot of infighting going on up north. So India was dealing with infighting allies on one hand, and with a very clear adversary on the other, who was under the pressure of [Pakistan’s] ISI.

That was a moment when India realised it cannot remain disconnected with the Pashtun belt of Afghanistan, so to say. It cannot not have any presence in south and east Afghanistan, and not just be restricted to the non-Pashtun communities in the north and the west.

That realisation had a very strong role in India’s expansion of outreach in these areas using developmental programmes and projects after 2001. By 2004-05, it became clear to indian policymakers that the Taliban is actually using bases in Afghanistan for shelter and might mount an insurgency in years to come.

That is when certain figures in India’s policy and security establishment take a call that it’s important to understand what the sources of the endurance of the Taliban are. Are we looking at the rise of the same kind and caliber of Taliban as in the 1990s? There was an interest in learning the workings of the Taliban.

By 2010-11, this becomes a bit more formalised. You have a sitting national security advisor open to talking to elements perceived to be close to Taliban. And that outreach did take place. But it was never taken up in earnest at an official political policy level, in which India would advocate talking to the Taliban. Then the concern was that such a position would alienate allies in Kabul. President Karzai was deeply averse to that kind of outreach.

Now is a situation when a lot of power holders in Kabul, part of the mainstream government, tell India to have those channels with the Taliban, just the way Iran does, just the way the Americans have. But we see a lack of interest or perhaps capacity and capability to push that agenda.

How do you assess India’s capacity to understand and engage with Afghanistan today?

In MEA, in R&AW and even India’s armed forces… I don’t think there is a lack of expertise on Afghanistan. Yes, of course, this is a community both within the government and outside that can be strengthened. In the larger context, India’s diplomatic corps are really small, given India’s ambitions and aspirations, but that is across the board – not just with Afghanistan.

But expertise isn’t really the handicap here. I think the serious handicap comes when policy suggestions reach the political leaders. I think there is not much interest. There is a very deep conservatism, to not explore things which have any risk associated with them.

What is surprising is that, despite there being officials who have in private expressed a desire to have channels with the Taliban, and wanted to explore how trust can be built, the political leadership have not shown that kind of interest.

It’s difficult to gauge whether that’s for ideological reasons, whether the political leadership is much more comfortable with partisanship vis a vis Pakistan, and by corollary in Afghanistan.

Is that surprising to you, given that the External Affairs Minister is a former diplomat?

No.

The minister right now – despite his background as an accomplished, seasoned diplomat who for a long time was considered a forward-looking pragmatist [willing to] break taboos in India’s foreign policy thought and practice – is more of a political speaker than a diplomat.

That’s something we’ll have to accept whether people like it or not. He is a politician first right now, and I think his calculation is that of a politician. I don’t want to go into details of who controls ultimate political power in New Delhi, but there would be limits even if a foreign minister would be open to these ideas of how far they can go.

You wrote a piece about this, so let me ask: What are your prescriptions for how the Indian government should proceed?

I should give credit to my colleagues Shreyas Shende and Rudra Chaudhuri, who wrote a very elaborate policy recommendation piece on India’s policies in Afghanistan.

The key points are: India needs to have an empowered special envoy focused on Afghanistan. Perhaps the individual and their office may cover Pakistan but that doesn’t need to be the case. But on Afghanistan, the envoy needs to be given a political mandate to reach out to everyone including the Taliban, on the ground and outside.

It’s very important for India to gauge the possibility of serious, enduring dialogue. This is not an endpoint. This envoy and that kind of commitment would allow India to see how far it can go ahead in securing interests with the Taliban, but it will also have a tempering effect on the Taliban.

This would mean talking to the Taliban, but also supporting the Afghan government and the national forces. In the piece I offer the contrast between the republic and the emirate. The republic is embattled and needs serious support. India, as a regional power, as a very important neighbour committed to democracy is committed to a republic over an emirate, can do more even in its current restricted capacities to support the republic.

This is where I think India can play a very important role, through a special envoy, to both offer more material assistance and political assistance to Kabul, while also opening outreach to the Taliban and somehow tempering its behaviour.

One reason why I think India might be a little more successful than the Americans on this count is: There has always been a sense within the Taliban and in Rawalpindi that at some point, the Americans will lose interest and leave. And that was prescient, coming from the experience of the Soviet Union.

Beyond a point, for big powers like Russia, America, even China, to operate in Afghanistan is not feasible forever. But for immediate neighbours like India, Pakistan and Iran, you can’t wait these countries out. They’ll always be there. This is the fact that can really be impressed upon the Taliban.

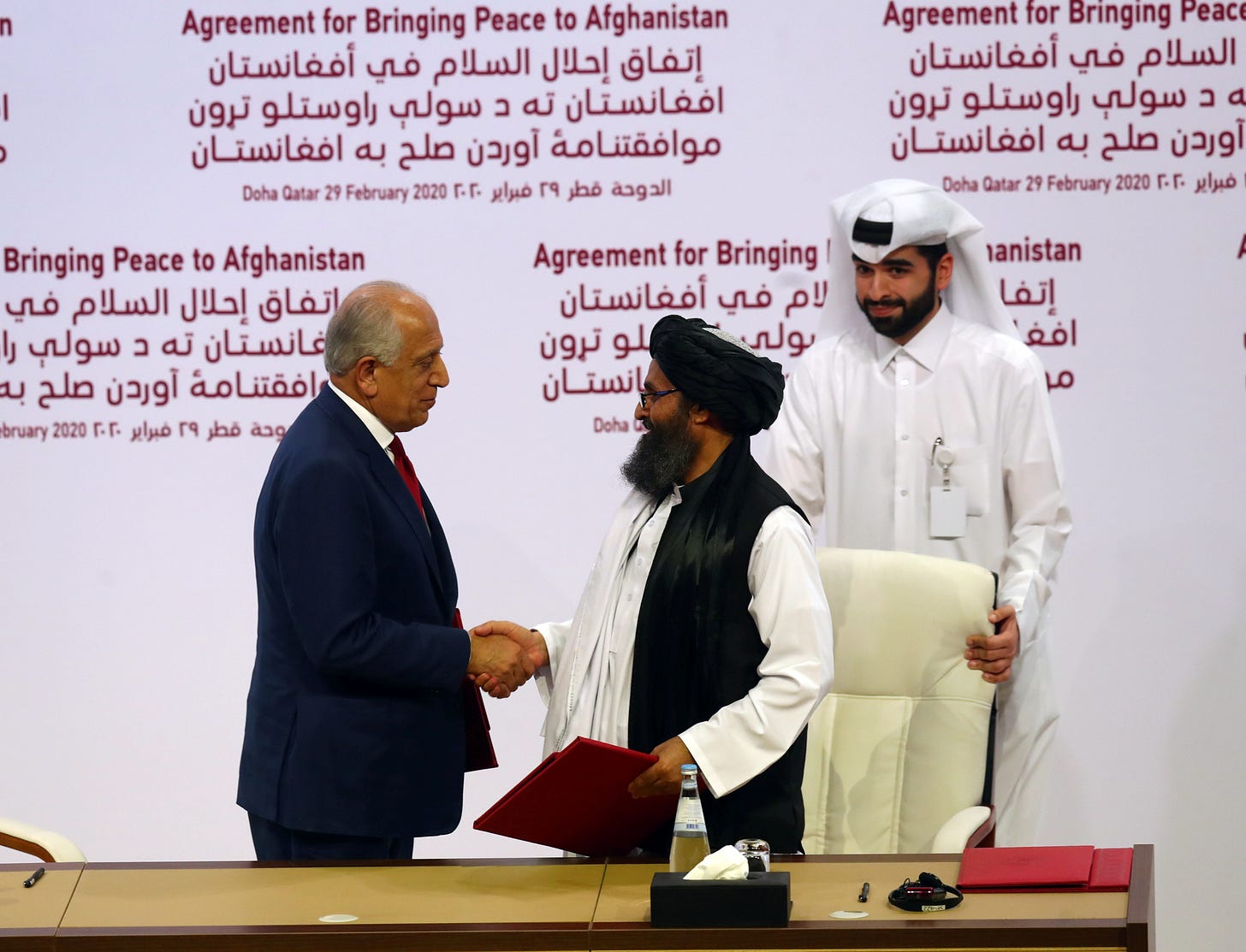

And I think the decision on Article 370 - I’m not going into the merits or lack of it – but that decision unsettled the Afghan talks in August 2019. The whole process going on in Doha had to be stopped, and the US Special Envoy to Afghanistan Zalmay Khalilzad, flew the very next morning to Delhi to understand what is going on.

So there are levers that Delhi can play in tempering the Taliban’s behaviour. The Taliban’s statement then was very clear – it wanted to stay away from the India-Pakistan rivalry. That was an interesting signal for India to take note of and build upon, perhaps, but we haven’t seen that happen.

To change tack a bit then, you spoke of the ‘Najibullah Model’ [in which India perhaps over-invests in one leader] and how that’s not the case in Afghanistan any more. But is India making the same mistake in Bangladesh or in Myanmar?

I think in Bangladesh, less so perhaps than in Myanmar. I grudgingly admit, even though I’m critical of India’s ever increasing reliance on Sheikh Hasina, who’s running a one-party state with a veneer of democracy on top of it, is that there is some degree of influence and a lot of leverage that New Delhi enjoys.

The problem is that it has not translated into deepening of democracy in Bangladesh. That has to do with the structural make of Bangladeshi’s polarised, bifurcated, violent body politic, but also India’s partisan stand in supporting one aspect of that.

The two years before 2009 there was a caretaker government, and at that time India realised it cannot bank on Khaleda Zia or the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, perhaps for historical reasons. India found Awami League’s secularism more appealing, and more than that, Awami League’s dependence on India was most appealing.

Sheikh Hasina’s experience of having lived in Delhi, in Pandara Road after the assassination of Sheikh Mukib in 1975 for six years before she went back… those are the kind of levers that impressed India the most to continue supporting the Awami League, however problematic their political practices might be.

With Bangladesh, the concern is more long term. As was visible with the recent visit by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, you can have a meaningful strategic partnership but there is still very potent, violent protest, both against Sheikh Hasina and by corollary, the idea of India in Bangladesh.

To overcome that structural mistrust among wide sections of Bangladeshi society should be and must be the key long-term strategic goal of India. And that is where I think perhaps we can learn from Afghanistan, where excessive focus on partisan support to one element instead of a diversified strategy is something that does not yield results in the long term.

Do you think there is recognition in the Indian establishment of this over-reliance on Hasina?

In some sections, there is. But, right now, India’s foreign policy bureaucracy and India’s security bureaucracy are undergoing a huge transition, in which they are dealing with intense interference by political leadership across the board.

For them to navigate rationality and what is in the long-term interest of the country, not just with Bangladesh, with the domestic political impulses which shape these policies is a very difficult balance.

How do you diversify relationship in a meaningful way – and I’m not talking about photo-opos that show India open to talking to the BNP or even the Taliban for that matter – when you have senior political leaders, whether it’s a home minister or someone else, making statements which go fundamentally against the existence of the people of Bangladesh, whether they are in India or elsewhere?

There are some very strong statements that have been made in the recent past, and they really limit the scope of what the foreign policy bureaucracy can do to diversify the relationship, even in a country as close and intimately linked to India as Bangladesh.

If there is ever a moment when the foreign policy bureaucracy don’t realise what is going on, the Bangladeshis take the onus and remind them that the issue of Article 370 and its after-effects is not resolved, the issue of movement of people is not resolved. It’s not an immediate concern, but there’s no lasting solution either.

We have papered over these differences, and focus on connectivity and roads. But no amount of money and connectivity can reduce the political salience of these ideologically driven agendas which have come to harm India’s relationship with Bangladesh in recent years.

Well, I wonder now that the West Bengal elections are over whether that opens up some space for change. On Myanmar, then is India relying too heavily on its connection to the military junta [known as the Tatmadaw]?

With Myanmar, I’m a bit more hopeful.

If you were a diplomat in Delhi, looking at Bangladesh and Myanmar, there is a structural bias in favour of Bangladesh. You would be spending much more time on Bangladesh than Myanmar. There is a serious capacity issue, unlike Afghanistan where there are capabilities but a lack of intent.

With Myanmar, there is a serious lack of capacities and capabilities in a material sense, but also in terms of a very basic intellectual grasping of the complexity of the country. I don’t want to say that people don’t understand the complexity. There are many officials, scholars, journalists who do understand the nitty gritties of various ethnic armed organisations, their own agendas, their relationship with the Tatmadaw or the NLD.

But that has not often translated into an enduring learning environment for India’s policy making circles. We are taking decisions based on cartoonish imagery, wherein we have decided that because India failed to support the democracy movement in 1988 after the protests, that means we’re condemned to dealing only with the military junta.

This is when one struggles. The narrative that the Tatmadaw has been supportive of India’s security interests in the North East or in ensuring stability and allowing India to have better connectivity to Southeast Asian markets, or better connectivity via the Kaladan project to the North East, is simply incorrect. The evidence suggests otherwise.

On the security front, this has always blown hot and cold. They’ve done some operations. But, a lot of the security initiatives that India took to manage the insurgent landscape in the North East was unilateral, not bilateral.

That one moment when insurgent violence was at its peak in Assam and Nagaland in the late 1980s and 1990s, India had to seek support from the Kachin Independence Army and other ethnic armed organisations to undertake operations in Assam, like Operation Bajrang and Operation Rhino.

And ever since, there are hundreds of camps across the Indo-Myanmar border, none of these camps were actually targeted by the Tatmadaw. When they had the capacity, they didn’t have intent. When they had the intent, they didn’t have the capacity.

So this narrative that the Tatmadaw is so important for India, in a security sense for the North East is misinformed. And at least I and some of my colleagues have struggled to change that narrative, pointing out that they’re important, but not panacea. The relationship is suboptimal at best.

They have of course extradited some 22 odd insurgents, some low-level, some mid-level a couple of years ago. But that’s very little after decades of giving them armed supplies, this is what they give, which is of limited operational consequence for India.

They’re not budging. India is just relying on other countries, like ASEAN and China and Russia to play their cards, and will then see how they can deal with it.

Having said that, I’ve seen from the ministry that they recognise the risk of having a unilateral, partisan pro-junta policy. The formation of the national unity government, however faction-ridden it is, the recent creation of the People’s Defence Force, and the military capabilities demonstrated by the Kachins and the Karens shook India a little bit.

It has surprised India to realise that if a political solution is lost, we are looking at a serious intensification of Myanmar’s long-standing civil wars. And a lot of them will be on India’s borders.

You’re looking at a moment when the coup has destabilised your border, which you’ve worked as part of your Act East policy to stabilise for years. And still, there is no diversification of strategy for India to be part of the process of resolving the situation. I think that is really worrying.

If I had to flip the question – what would India be risking by diversifying away from the Tatmadaw?

The risk would be that India wouldn’t be able to translate that diversification into a politically coherent outcome. That means you’re dealing with a fragmented country in the neighbourhood, and it does not allow you to pursue your strategic interests as you sought.

India’s image as regional power would take a dent. The learning has been from the Chinese, who tried to negotiate on the Rohingya issue and failed to resolve anything.

But, if ASEAN fails, and it seems to be failing now, you are anyhow looking at a situation with de facto autonomous regions run by ethnic armed groups where Tatmadaw’s writ does not run large – in Rakhine, in Kachin, even in Sagaing.

How do you deal with such a fractured policy? If you don’t talk to them, you will be left with a civil war or state collapse on your east. And that would have very serious consequences on the viability of India’s Act East policy.

But if you diversify, you might still succeed even in a limited way to have some political resolution, even if it’s not a grand bargain. It will allow India to have a relationship with ethnic armed organisations, which might not disable India from pursuing its long term interests.

Even if Arakan Army exists, it might not be kidnapping your engineers trying to build the Kaladan Road. They might not harm your interest in a direct sense. So you have some leverage on the ground to exercise in a political sense, which right now you simply don’t have.

We’re running out of time, so: What advice would you have for students and scholars interested in this space?

First, develop skills and tools to delve into the empirical details of India’s relationship with neighbouring countries. The devil lies in the details, as I discovered while doing the Afghanistan book.

Even in Myanmar, Bangladesh, Nepal and Sri Lanka, India is doing a lot more than newspapers would perhaps tell you.

And sometimes the best way to understand India’s foreign policy is not necessarily to talk to retired diplomats, however important they are as a resource, but to talk to the recipients of India’s foreign policy practices.

I learned more about India in Myanmar by talking to the Kachins, the Karens, the Rakhine nationalists, to the Tatmadaw, to the NLD politicians, than I learned by talking to officials in India. If you’re interested in the region, go out of New Delhi to understand what it is doing on the ground.

That gives us a much better, nuanced understanding of the disjuncture between India’s ambition as a rising power and its reality.

Also, archives are deeply under-explored, even if there is an appreciation of their existence. There are archival documents that will give you a good sense of India’s cover ops which people have never utilised. There is a lot of empirical material to be explored, analysed and processed.

Which takes me to my second point: I would encourage everyone to use that and advance disciplinary debates, theoretical debates, in whichever discipline you belong to.

A lot of the theoretical debates do not reflect the non-Western or Indian context, simply because the empirical richness that scholars working on more developed contexts can bring to bear does not exist.

So use empirical knowledge and expertise to actually advance conceptual debate and develop disciplines, which can develop a lot more than we know and be much more nuanced in their modeling, concepts and arguments based on Indian and South Asian experiences.

What misconceptions do you find yourself combating all the time?

Misconceptions are often more powerful than what experts like to believe about their own knowledge of topics in informing policy. So I’ve come to respect misconceptions as an existence that we can’t battle beyond a point.

In a larger sense, right now, facing the pandemic second wave in India, I think the biggest misconception for people to resist against is this misplaced, outsized conception of India being a huge power just because it exists, in its territorial, demographic grandeur.

That is not the case. There is a long way for India to go to be considered a serious power. Of course, it is important in many ways, in the Quad, and with India taking on the Chinese, whether in Ladakh or elsewhere. These are important narratives.

But it’s important to be real about India’s capabilities. And the fact is divisive politics does not make India a power. It actually militates against India’s own aspirations. And the fact that people have come to think that India is being respected across the world because it is more muscular today – that’s just simply wrong.

Countries outside have their own issues, but they can also see the issues that are inhibiting India’s own rise in very clear ways. You cannot fool the whole world about who you are.

That’s my biggest peeve, as we deal with the pandemic, as we lose our loved ones, where you can see the political leadership trying to focus on image management, rather than actually the substance that it has to offer to its citizens. Forget the world at large.

Finally, do you have three recommendations for readers?

The Greater India Experiment: Hindutva and the Northeast, by Arkotong Longkumer

Shadow States: India, China and the Himalayas, 1910-62 by Bérénice Guyot-Réchard

The Craft of International History: A Guide to Method, by Marc Trachtenberg