The Political Fix: Will Quad membership and a ‘minilateral web’ protect India against China?

A newsletter on policy and politics from Scroll.in.

Welcome to The Political Fix by Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, a newsletter on Indian politics and policy. To get it in your inbox every week, sign up here.

Have you checked out Scroll.in’s new project, Common Ground, which offers in-depth and investigative reportage on our neglected commons? Get those stories in your inbox every Wednesday by signing up here.

And if you’d like to support the work we do at Scroll.in, contribute to the Ground Reporting Fund.

The Big Story: Mini driver

Prime Minister Narendra Modi returned to India on Saturday, after a short but significant three-day trip to the US, to a Bharatiya Janata Party-arranged welcome that, as one Twitter user quipped, suggested they were afraid he wouldn’t come back.

Among others things, Modi addressed the United Nations General Assembly, held his first in-person meeting with US President Joe Biden and Vice-President Kamala Harris, met a number of American CEOs and business leaders, bilateral meetings with the heads of Australia and Japan and – most importantly – attended the first in-person Quad summit.

The Quad is a grouping of the US, Japan, Australia and India that was first formed in response to the devastating 2004 tsunami, but has turned into a non-treaty based partnership between democracies focused on containing China over the last few years.

The Quad gathering led to a long joint statement – featuring the China-focused phrase “undaunted by coercion” – a “Quad Principles on Technology Design, Development, Governance, and Use” document and a fact sheet. Among the agreements between the heads of state was an agreement to bolster supply chains of semiconductors, to cooperate on post-Covid recovery plans and to coordinate policies on Afghanistan.

But, as political scientist Christopher Clary noted, the main deliverable was the summit itself. Just getting these four leaders in one place and agreeing on a long joint statement, sends a clear message. Brookings’ Tanvi Madan writes,

“To understand how far the Quad has come in a short period, consider its ministerial just a year ago. No joint statement emerged, and Indian documents would not even use the term “Quad.” But, on September 24, the leaders of Australia, India, Japan, and the US held their second summit in six months, this time in person...

The Quad is never going to meet everyone’s expectations — it is a vessel into which many hopes are placed, and it cannot and should not be a one-stop shop. But the summit and deliverables signal that the countries today have a greater willingness and ability to act together.”

The path traveled by India to get here has not been straightforward.

Historically, India has always embraced its non-aligned reputation, even if New Delhi was actually leaning one way or another, and the country refused to be drawn into the Cold War-era framework of “treaty allies” that provide mutual security while constraining foreign policy choices.

Indeed, in the first few years of his tenure, Modi indicated that India would attempt to retain this approach, in the hopes of being able to receive technology and military support from the West without having to say no to funds flowing in from China.

But the years of US President Donald Trump’s administration, the Covid-19 crisis and Chinese belligerence leading to the first deaths in four decades at the Line of Actual Control have clarified India’s thinking. New Delhi’s response has not been to shed its strategic autonomy and turn into an ally of the US.

Instead, India is hoping to take advantage of groupings like the Quad – minilaterals – that allow countries more flexibility in addressing common threats, without necessarily hemming them in by expecting all-out convergence on foreign policy goals.

As Indian External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar argued in an important speech earlier this month,

“While the entire region grapples with different capacities and new approaches, some are likely to make more progress together than others. The fact is that the days of unilateralism are over, bilateralism has its own limits, and as the Covid reminded us, multilateralism is simply not working well enough. The resistance to reforming international organizations compel us to look for more practical and immediate solutions. And that, ladies and gentlemen, is the case for the Quad.”

The Quad isn’t the only immediate Indo-Pacific grouping in town. There is the India-Australia-France trilateral, which may not be meeting anytime soon, but also the India-Australia-Indonesia trilateral, the India-Australia-Japan subgrouping within Quad partners, and more.

The Observer Research Foundation’s Rajeshwari Pillai Rajagopalan took a look at the rise of these Indo-Pacific minilaterals in an issue brief, arguing that “given the contentious nature of global-power relations and the difficulties in developing consensus, minilaterals carry a huge advantage of building shared viewpoints, which can gradually be taken to larger, more traditional formal platforms”.

Rajagopalan added, “China has helped the cause. Beijing’s aggressive behaviour has allowed for focused attention and building support at the domestic or regional level, and the Quad-like formats and Indo-Pacific strategies are gaining more takers.”

Of course, what permits groupings like these to flourish is US President Joe Biden’s decision to re-affirm the Trump administration’s laser sharp focus on Beijing as Washington, DC’s principal threat. Members of Biden’s team have argued that successfully carrying out former President Barack Obama’s “pivot to Asia”, which has since become an Indo-Pacific strategy, involves embracing new forms of cooperation that don’t necessarily fit into the allies-or-not approach of the Cold War.

Brookings’ Rush Doshi and Kurt Campbell, who was later picked to be Biden’s Indo-Pacific coordinator, explained the framework in January:

“The United States will need to be flexible and innovative as it builds partnerships. Rather than form a grand coalition focused on every issue, the United States should pursue bespoke or ad hoc bodies focused on individual problems... These coalitions will be most urgent for questions of trade, technology, supply chains, and standards...

The purpose of these different coalitions – and this broader strategy – is to create balance in some cases, bolster consensus on important facets of the regional order in others, and send a message that there are risks to China’s present course. This task will be among the most challenging in the recent history of American statecraft.”

AUKUS, the grouping of Australia, the United Kingdom and the US, announced last week is one answer to this effort. The trilateral arrangement to provide Australia with American nuclear-powered submarines that will allow it to project power in waters where China is increasing its presence, suggests that the long-standing allies are still working on efforts to update their partnerships to the new world order.

Although there has been some handwringing from observers in India about the Quad now having to play second-fiddle, few see AUKUS as anything but a force-multiplier for the broader strategy that aims to put a check on Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific.

The angry response from France, which was originally supposed to provide submarines to Australia, however, underlines Campbell and Doshi’s argument that this task will be challenging. A conversation between Biden and French President Emannuel Macron seems to have lowered the temperature for the moment, though there remain questions of how Europe will respond to this Anglosphere assertion – as we discussed on the Political Fix Q&A this weekend.

For India, however, keeping partners like France invested in the Indo-Pacific is not just important, it may represent a new aspect of this minilateral-era:

“The transatlantic fissure has also pointed to something inconceivable – that India could emerge as a potential bridge between different parts of the West,” wrote C Raja Mohan. “India’s solidarity with France at a difficult moment is rooted in New Delhi’s conviction that preserving the West’s unity is critical in shaping the strategic future of the Indo-Pacific. Who would ever have thought India would be championing Western coherence in Asia?”

Read also

Nahal Toosi on why Biden’s need to work with India versus China is a challenge for the White House, given Modi’s record on human rights. It was no wonder that Modi decided to begin his UNGA speech referring to India as the “mother of democracy” and his attempts to talk up values that would be seen as liberal, and are often in stark contrast to those espoused by his party members back home.

“Can minilaterals deliver a security architecture in the Indian Ocean?” by Kate Sullivan de Estrada, building on this fascinating effort by Arzan Tarapore to study India’s strategic choices based on unlikely alternative futures.

“AUKUS, or Quad Plus? Probably both. If the bigger picture is to set up a web of networks to put China in place, there could soon be other groupings – which could potentially include South Korea, Indonesia, Israel, UAE etc,” writes Indrani Bagchi.

Pranay Kotasthane on the important plans for the Quad to provide resilience to the semiconductor supply chain.

Frédéric Grare and Manisha Reuter offer useful scorecards on how various European nations look at the Indo-Pacific.

“The job of developing new Asian security measures clearly cannot be outsourced to the old Anglosphere alone,” writes James Crabtree. “The US and its partners would be wise to continue to ensure buy-in elsewhere around Asia, including among the more nervous nations of Southeast Asia.”

Three big, not too surprising predictions from CNBC’s project on the Quad.

Linking In

If you haven’t already, read all five parts of Arunabh Saikia’s Crime and Punishment series, in which he looks at Uttar Pradesh Chief Minister Adityanath’s record on law and order, and what that tells us about the state heading into elections next year.

Arunabh Saikia also reported from Assam, where an eviction drive turned fatal – and gruesome – with visuals of a police photographer brutally attacking a protester. Ipsita Chakravarty explains why this incident is not a one-off, but has state sanction. And for context, read Saikia’s deep-dive from last year on the politics around evictions in the state.

Smitha Nair, who once hosted Scroll.in’s Your Morning Fix, has a new weekly podcast, called the Big Story, Explained. Last week, she took a look at Tamil Nadu’s position on NEET, the medical education qualifying exam that the state has argued is privileging elite students.

A series of pieces on the Delhi Master Plan 2041 examines ideas about slum rehabilitation, making the city friendlier for workers and more.

Tabassum Barnagarwala explains how Bihar achieved its huge vaccination numbers on Modi’s birthday – by delivering ‘offline’ doses over the previous days and then uploading the data on the birthday to make the numbers seem larger.

Can’t make this up

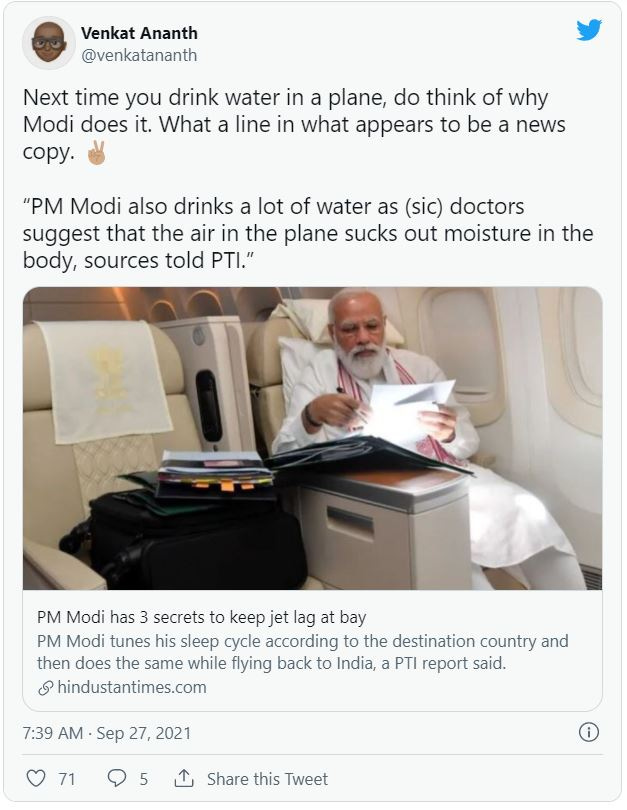

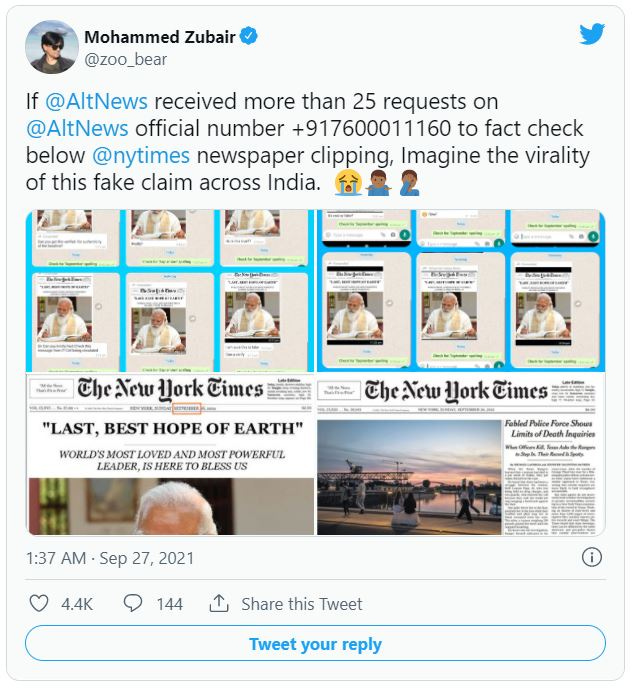

The Modi image-making propaganda teams were out in force over the weekend:

Thanks for reading the Political Fix. Send feedback to rohan@scroll.in.

Support our journalism by contributing toScroll Ground Reporting Fund. We welcome your comments at letters@scroll.in.