The Political Fix: Why is India still pursuing ‘tax terrorism’ cases against Cairn and Vodafone?

Plus, lots of links.

Welcome to The Political Fix by Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, a newsletter on Indian politics and policy. To get it in your inbox every week, sign up here.

Reminder: Our small team wants to cover the big issues. That is why we are appealing for contributions to our Ground Reporting Fund. If you’d like to assist our effort, click here.

The Big Story: Tax terroir

“Humiliating”, the Business Standard called it. “Time to put an end to this sorry matter,” said the Indian Express. Hindu BusinessLine called it “unfortunate and embarrassing.”

That is just a smattering of the editorial responses to the news from last week that British oil company Cairn Energy successfully petitioned a French court to freeze real estate properties in Paris belonging to the Indian government valued at around $24 million. The company said the court order was a “necessary preparatory step to taking ownership of the properties and ensures that the proceeds of any sales would be due to Cairn”, based on the $1.2 billion arbitration award it won in 2020 against tax claims by the Indian government.

More bad news could be on its way. Cairn has filed similar cases in eight other countries, including the US and the UK, which have signed the 1958 New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards.

It is hoping to have courts freeze other Indian assets located in those countries, like bank accounts and ships owned by the Shipping Corporation of India. Its decision to sue for Air India’s assets in New York has already hurt the government’s plans to sell the national carrier.

Even more alarmingly, two other companies with similar grouses and arbitration victories against the Indian government – Vodafone and Devas Multimedia – could follow suit. As the Business Standard editorial adds, “Cairn Energy itself is a small player; however, it might well sell its rights under the arbitration onward to a third party with more resources to pursue the claim. That would certainly be a nightmare scenario.”

The entire episode is a classic example of how, in India, you can campaign in polemics but still end up governing in prose.

Vodafone, Cairn and Devas

In 2007, the Indian tax department sought to levy capital gains tax on a transaction in which the Netherlands-based Vodafone bought a Cayman Islands-based firm that controlled the Hutchison telecommunications network, then operating in India. Vodafone disagreed, arguing that India couldn’t tax transactions taking place between two companies based elsewhere, even if the underlying assets were all in the Indian market.

In 2012, after the Bombay High Court took the side of the Indian income tax department, the Supreme Court went the other way, ruling that Vodafone did not need to pay the billions of dollars in taxes.

But the Congress-ruled Indian government was not having it. The Supreme Court’s order was circumvented by a law passed in Parliament that clarified the interpretation of capital gains tax, and allowed the tax department to retrospectively reassess transactions going back to 1962.

This retrospective tax turned into a political firestorm. The Bharatiya Janata Party described this as “tax terrorism” and promised that it would not take the same line when in power. Yet the law remains on the books, and Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government has continued to pursue the case against Vodafone and a similar demand for capital gains tax against Cairn Energy for transactions dating back to 2006.

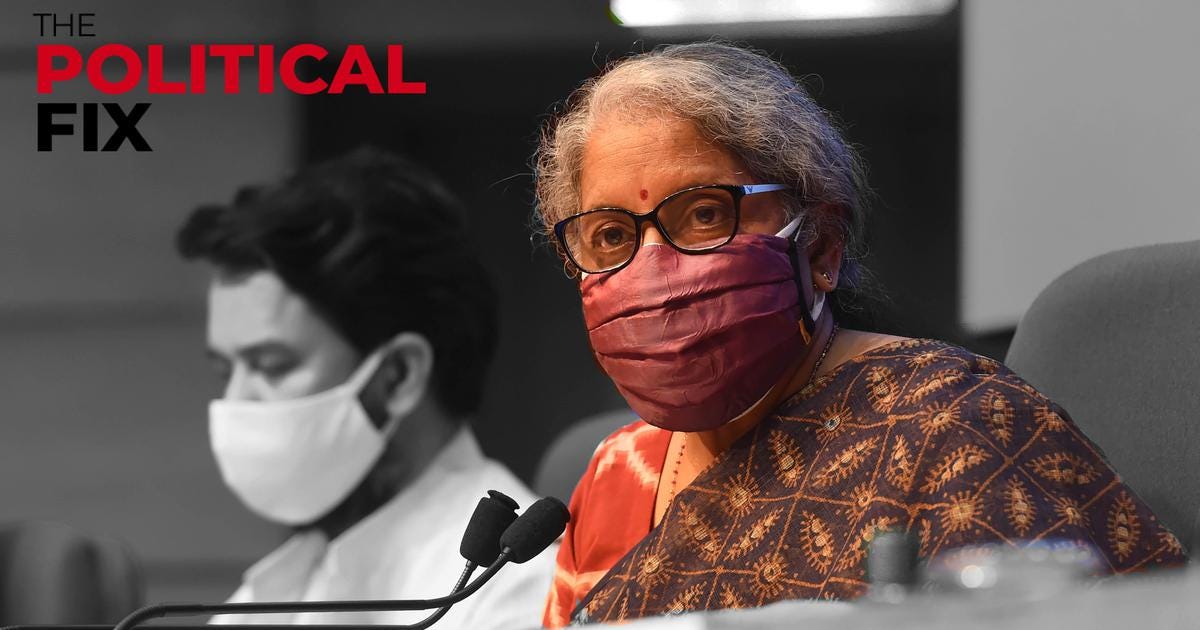

Former Indian Finance Minister Pranab Mukherjee

As Pranab Mukherjee, the former Indian president who was finance minister when the retrospective taxation law was passed, wrote in his memoirs, Ddespite the angst that my proposal generated at that time, and even now, both from within my party and outside, I wonder why every succeeding finance minister in the past five years has maintained the same stance.”

The Devas case is slightly different, involving not taxation but a contract between the company and the Indian Space Research Organisation-owned Antrix for the lease of satellite spectrum that was annulled in 2011. It is mentioned alongside the other two because, as in those cases, the foreign investors in Devas managed to win an international arbitration award against the Indian government. Taking a cue from Cairn, they have now sought to take over some of Air India’s assets in the US to enforce the order.

In short, the BJP, after accusing the previous government of “tax terrorism” and creating an unfavorable environment for business, has chosen to disregard international arbitration decisions and to continue pursuing the companies. As a result, it is now facing the ignominy of having to fight for Indian assets to not be frozen in several foreign jurisdictions, even as its plans for privatising Air India are in danger.

As TN Ninan writes,

“The BJP fought the 2014 elections with a stand against ‘tax terrorism’… But, seven years later, its continuing ‘terrorism’ has left the government with considerable egg on its face. As with domestic tax cases, the government may well believe it has a case even if it has lost in court. But there is a difference. Domestically, the state pays no penalty for converting the process into punishment. Internationally, once the verdict has gone against you, the state has to accept the consequences of its actions.”

Treaty troubles

Why is it doing this, when it knows the discouraging message such actions send to foreign companies and investors?

Some have argued that in both the Vodafone and Cairn cases, India was right to tax the companies, simply because they were resorting to technical loopholes to avoid paying their dues.

But Modi’s government seems to have taken a different tack. It has repeatedly spoken out against retrospective taxation. At the same time, the government has taken issue with the basis on which the arbitration decisions were made – that India’s tax demands violated existing bilateral investment treaties between the countries, which promised to treat the companies fairly and equitably.

As far as India is concerned, bilateral treaties cannot supersede the country’s sovereign right to impose taxes of any kind, even if the companies feel they are unfair.

In an interview earlier this year, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman explained,

“I am expected to keep up to fight for the sovereign right of India to tax, but where has that led us? You are fighting on a cause where you showed that Indian government is probably vengeful… Although when I am in government, I have to remember that if there are questions on the sovereign right of India to tax, I will have to stand up. That does not mean the retrospective amendment was right.”

Indeed, so concerned was Modi’s government about the danger posed by international arbitration based on bilateral investment treaties that, in 2017, it cancelled existing agreements with more than 50 countries that had been signed mostly in the 1990s as the economy was being opened up and began to renegotiate terms.

In 2016, it put out the draft of a model investment treaty text, significantly reducing protections to foreign investors that might seek to go to international arbitration. However, it has struggled to convince countries to sign up to the new terms, with just a handful of nations agreeing.

“India’s model BIT [bilateral investment treaty] and, in fact, its entire approach toward BITs have inherent contradictions,” wrote independent advocate and arbitration counsel Abhishek Dwivedi in 2020. “The Indian approach to BITs is riddled with inconsistencies that threaten to defeat the entire purpose and may, in fact, fail to achieve the anticipated objectives.”

What is evident is that, even if the government’s “taxation as a sovereign right” position appears to put it on more sensible ground than a defence of the retrospective tax, its tactics have not achieved much. Attempts have been made to settle the matters directly with the various companies and investors in each of these cases, but they have mostly gone nowhere.

The state has shown some flexibility – not getting in the way of Vodafone’s merger with Idea cellular in 2018 despite the taxation questions. Yet its legal approach has been criticised both on tactics and timeliness, and will now face challenges in nine different countries where Cairn has filed suit.

Buoyed primarily by the huge investments into Reliance in 2020, some have argued that all the claims of India’s reputation being hurt have amounted to little and that foreign companies will still seek out opportunities in India. But India’s struggle to sign investment treaties over the last few years suggests that there is at least some hesitation on the regulatory front.

As the Cairn fight gets even more high-pitched over the coming months, with Vodafone and Devas potentially jumping on the bandwagon, will India have to grapple with a harsher fallout from its decision to disregard international arbitration verdicts, or its much criticised legal tactics?

For more background on this, read:

Explained: Why is Cairn going after Indian assets?

Antrix-Devas, BIT Arbitrations, and India’s Quixotic Approach

Flotsam and Jetsam

I wrote about the big Cabinet reshuffle that Modi carried out over the past week, dropping 20% of his ministers and inducting a whopping 36 new faces into a much bigger Council of Ministers – as clear an acknowledgment of the need for a reset halfway into Modi 2.0 as we will get.

Shoaib Daniyal looked at whether the Modi government’s relentless focus on inflation control is now falling apart.

India has pulled out from its Kandahar consulate in Afghanistan, as the Taliban continue to make major gains. Its diplomats are still on site in the capital, Kabul, and Mazar-e-Sharif, though there are already concerns about the ability to resist in the latter.

Although cases remain low around the country, the “R-number”, which tells us how many are being infected by one positive Covid-19 case, has begun to trend upwards, sending an early warning about what may be coming.

The Uttar Pradesh State Law Commission issued a draft population control bill proposing a two-child policy that many see as the first in a series of legislative moves ahead of elections next year. Meanwhile, local polls in the state, in which the BJP claimed victory, were hit by violence and questions about why .

Why did India need a brand new Ministry of Cooperation, headed by Amit Shah, asks M Rajshekhar?

Can’t make this up

Thanks for reading the Political Fix. Send feedback to rohan@scroll.in.