The Political Fix: Why India will have a hard time navigating its way out of the Covid-19 lockdown

A weekly newsletter on Indian policy and politics from Scroll.in.

Welcome to the Political Fix by Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, a weekly newsletter on Indian politics and policy. To get it in your inbox every Monday, sign up here.

If you want journalism with spine not spin, consider supporting us either by subscribing to Scroll+ or contributing to the Scroll.in Reporting Fund.

The Big Story: No happy ending

On March 24, Prime Minister Narendra Modi announced that India was going into lockdown for three weeks in an attempt to prevent the spread of the new coronavirus. The initial result was chaos and a huge migrant exodus, as we wrote about two weeks ago.

As the end of that period approaches, India’s leaders and policy-makers are faced with a difficult decision: how do you end a national lockdown even as the number of people infected with Covid-19 is still growing?

As we have pointed out a few times, India’s lockdown is quite different to the restrictions that have been elsewhere, particularly on the West. For one, it was put in place with almost no notice and is being enforced with much more violence.

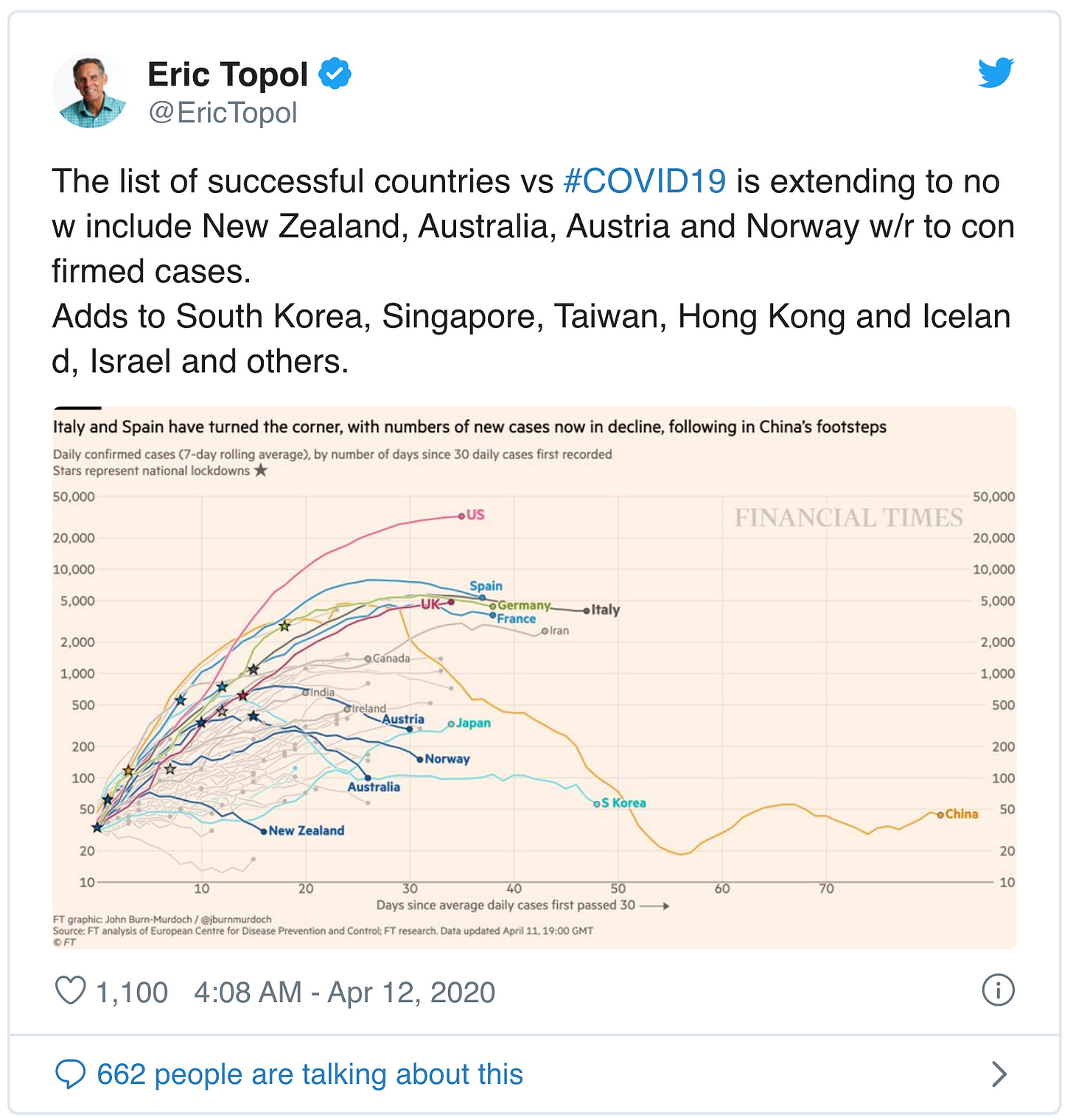

India’s lockdown also came extremely early into the curve of the virus.

Many other countries slowly ramped up their restrictive measures, culminating in full stay-at-home orders after hundreds of people had already died of the coronavirus.

When India went into lockdown, it had only around 500 confirmed cases and around 10 deaths. As the end of the three weeks approaches, India has 8,447 cases and 273 deaths.

From some angles, this is a good thing: India skipped the dilly-dallying that other countries went through before ordering full lockdowns in a way that might be more likely to break the chain of the virus.

It also takes into consideration India’s woeful healthcare system. After all, Prime Minister Narendra Modi noted that if the virus is allowed to spread, it could set India back by 21 years.

Since the virus tends to show itself in people a week or two weeks after infection, we will only know over the next 10 days or so whether the lockdown has helped flatten the curve.

Kerala, which was forced to move much quicker than most other states in India, offers some good news on that front.

But being “early” has two other effects.

First, it means India will find it harder to wait until it has “peaked” – or to even identify when that might be.

Lockdowns come at the cost of shutting down the economy and endangering livelihoods. Ideally, they are only in place for the duration when they can have the greatest impact on preventing further spread of the disease.

Countries in Europe are looking to end lockdown restrictions after they have hit a peak in the number of new cases and deaths per day. In India, where much more testing and clinical data is needed, it may be weeks before we even have an idea of when that peak might arrive.

Secondly, and more importantly, India’s “early” lockdown inverts what we consider normal: it makes lockdown the default – and everything else a relaxation.

In the West, countries slowly ramped up to stay-at-home orders and, as the United States makes evident, politicians desperately want to re-open the economy even as deaths continue to spike.

Although some Indian leaders have demanded a relaxation, others have appealed to the prime minister to extend the lockdown. Odisha, which has just 42 cases so far, was the first to unilaterally announce a two-week extension, deciding to stay locked down until the end of April.

Politicians see the lockdown as a blunt instrument, yet also the most powerful weapon they wield at the moment. It is a way to buy time to ramp up healthcare infrastructure and also seem as if they are doing something to take on the challenge.

After the migrant exodus at the start of the three-week lockdown, they are also keenly aware of the higher-order complexity that will come with attempting to open up – even in a staggered manner.

So, despite the damage it is doing to economies, most Indian leaders would prefer to keep their states shut – at least until there is more data about how the disease is spreading.

This situation won’t last forever, as the costs of the economy remaining shut start to become much more visible than deaths caused by the virus.

When he announced the lockdown, Modi said he was prioritising lives over livelihoods, saying “jaan hai to jahaan hai” (only if there are lives, is there a world to live in). Over the last few days, his office has sent the message that the new mantra is “jaan bhi, jahaan bhi” (roughly, both lives and livelihoods).

It seems likely that Modi will on Monday or Tuesday announce a two-week extension to the national lockdown, while also offering a blueprint for how the country will begin opening up gradually.

Key to this approach is the Cluster Containment Strategy that I wrote about this week. This seeks to aggressively contain the disease within various hotspots around the country, while other areas can begin a gradual relaxation of restrictions.

However, one renowned epidemiologist has flagged concerns about this approach: “Containment of the virus is an early manoeuvre, I am anxious that we are late... You can keep isolating people, and then supposing the virus keeps growing, you will have to isolate even more people.”

Hosts vs homes

Despite broad consensus over extending the lockdown, a clear fault-line is emerging: states that play host to migrant workers don’t want to keep them in shelters for much longer, and would prefer to see them go home. The home states, however, don’t want a sudden influx to overwhelm their healthcare systems.

The host states have been worried that this could lead to social unrest, as the migrants demand to be let home.

Dipankar Ghose and Liz Mathew of the Indian Expresslooked at the issue here:

“Sources said Maharashtra Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray made a forceful plea for arrangements to help stranded migrant workers travel home. He said, it is learnt, that it was the responsibility of the state to arrange for their safety...

States like Chhattisgarh and Rajasthan, too, suggested that people from their states stranded elsewhere be brought back or there could be “problems.” Kerala Chief Minister Pinarayi Vijayan said that if the situation wasn’t addressed, serious social unrest could take place and so the government must have a plan in place...

Not all states were on the same page, though. Jharkhand Chief Minister Hemant Soren called it a Catch-22 and said returning workers could bring the risk of infection. He left it to the discretion of the Centre and red-flagged possible law-and-order issues, if workers return amid the pandemic. This would necessitate the deployment of police or even the Army, he is learnt to have said.”

Centralised consensus

Prime Minister Narendra Modi made the announcement of a national three-week lockdown without consulting the states, raising fears that his handling of the Coronavirus crisis might lead to less federalism and more centralisation – which we wrote about on the Political Fix last week.

But his office has been at pains to show that any extension, which could lead to even more economic pain, will be based on the demands of the states.

Of course, this doesn’t mean that the Centre is transparently addressing questions raised by the states.

In a teleconference with chief ministers, Modi was silent about demands for more funds to states, and the Centre has not classified donations to individual Chief Ministers’ Relief Funds as counting towards mandatory Corporate Social Responsibility norms for businesses, despite the newly established PM-CARES being counted.

Meanwhile, it has emerged that the Centre still owes the states more than Rs 30,000 crore in Goods and Services Tax compensation dues alone.

Test free or die

India was permitting private companies to also test for Covid-19 and charge up to Rs 4,500 for each test, until last week, when the Supreme Court jumped into the fray. The court ordered that all Covid-19 testing should be free. However, it left it up to the government to decide how to implement this decision.

Many have described the court’s move as well-intentioned but misguided, arguing that if labs cannot even break even, they will simply stop testing. Indeed, in the absence of guidelines from the government, that is what happened in the case of some private lab chains, though others have decided to test for free at the moment despite no assurance of being reimbursed by the state.

Namaste Trump

First, India decided to ban exports of hydroxychloroquine, a malaria drug that India has recommended as preventive medicine for health workers coming into contact with coronavirus patients and US President Donald Trump has been pushing as a cure for Covid-19.

Then Trump got in touch with Modi, and publicly threatened retaliation against India for banning exports.

Soon after, India re-evaluated its export ban and said it had sufficient stock for domestic needs and would send HCQ to the neighbourhood and countries that are badly hit by Covid-19.

The end result – cooperation with the United States – may be a good thing. The sight of India buckling to Trump’s threats is not.

Flotsam & Jetsam

The Reserve Bank of India jumped into the fray with a number of bold moves, but gave little explanation for what guided its policy thinking. There is buzz of a bigger financial package from the Centre for small and medium business. India’s Health Ministry continues to inspire little confidence, relying on shoddy data and a lack of transparency in its interactions with the press.

In the middle of all of this a Karnataka Bharatiya Janata Party MLA decided to host a grand birthday party, a number of top Madhya Pradesh officials have tested positive and Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister suddenly decided to terminate the state election commissioner.

Recommendation Corner

Venkat Ananth is Bengaluru-based technology reporter with The Economic Times, who regularly pulls out interesting recommendations from all the corners of the internet. His most recent pieces looked at how the government intends to use Aarogya Setu, the contact tracing app.

Here are his picks:

“Besides working on stories, I’ve been using this time to catch up on a lot of reading and podcast listening.

I’m currently re-reading this 2004 book by Thomas Frank called What’s the Matter With Kansas, which quite presciently captured the rise of right-wing populism in the United States, twelve years before Trump happened. The book was at the heart of a lot of debate within American political scientists back then, and with opinions that said that there wasn’t any empirical evidence to what Frank wrote about. Well, I guess that question has since been answered.

I first read this book in 2017, when I thought we’d reached ‘peak populism’ but I think Frank’s book is an essential read for those trying to understand the evolution of conservative politics in the US.

Another book I’d strongly recommend is Antisocial: How Online Extremists Broke Americaby New Yorker staff writer Andrew Morantz. Essential reading for anyone trying to decode technology and politics. It’s a terrific deep dive on the so-called alt-right phenomenon. As someone who has reported on similar phenomenon on India, especially with the BJP’s IT Cell-based propaganda efforts, this makes a good reference points to compare notes, strategies, tactics and so on.

I quite like Deep Background, a podcast by Noah Feldman, a Harvard Law Professor and author. What I like about this podcast is the way Feldman brings an expert per episode to come and provide much needed, well, background — all kinds — historic, scientific, legal etc etc, on anything newsworthy.

My regular (almost daily) podcast picks would be — On the Media (WNYC Studios), Reveal (Centre for Investigative Reporting) and The Daily(The New York Times).”

Have recommendations for an article, book, podcast or academic paper that deals with Indian politics or policy? Send it to rohan@scroll.in. Previous recommendations from the Political Fix are collected here.

Poll toon

Ground Report

Although much focus has been on doctors who come into direct contact with Covid-19 patients, there are many other professionals who also take that risk and who desperately need to be given protective equipment.

Vijayta Lalwani has the story:

“A nurse who works in the casualty ward at Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar Hospital in Kandivali in North Mumbai said that nurses were being made to use one-ply surgical masks and HIV kits for the last five days despite making repeated demands for PPEs to the hospital authorities.

‘Before that we were wearing a plastic apron,’ said the 36-year-old nurse who did not wish to be identified. The nurse said that the hospital had not arranged for a separate accommodation for nurses or prepared a roster to give them time to go into quarantine after working for seven days. ‘They have only done it for doctors so far,’ she said.”

There is much more reportage and analysis of the Coronavirus Crisis on Scroll.in, like this piece on how hunger is on the rise in Haryana’s industrial belt, how intra-state migrants in Andhra Pradesh are hungry and homeless and how migrant workers in Telangana have been locked up in shelters.

Read all of our coverage here.

And if you need a break from all the hard news, there’s Art of Solitude, our series on the creativity that is helping people tide over these times.

If you enjoy this newsletter and our journalism, I have a request: To ensure we can continue to bring you all the reportage, analysis and other coverage that is vital in these times, we need your help!

You can support Scroll.in by contributing to our reporting fund or, if you are abroad, subscribing to Scroll+.

Linking out

How long can Indian firms last in current conditions without any support? Renuka Sane and Anjali Sharma, writing on the Leap Blog, find that “more than half of the Indian corporate non-financial balance sheet is unable to hold its breath for 90 days, under these assumptions. About a quarter of the firms will not be able to handle a 30 day interruption of revenues.”

Could India use public health as “the engine of a state-funded investment drive”? Andy Mukherjee argues on Bloomberg that New Delhi should use a massive healthcare push as the way forward considering manufacturing for a global market might become even harder.

How can India find the money to pay for the massive government expenditures that is needed? Arvind Subramanian and Devesh Kapur in the Business Standard lay out a whole menu of options, including foreign borrowing, public financing and even “printing money”. Read the first, second and third part of the series here.

Why did the lockdown cause a migrant exodus? How can India rebuild the economy? The Centre for Policy Research’s Yamini Aiyar is hosting a series of podcasts on Scroll.in that dig deeper into key issues surrounding the Coronavirus crisis. Go check out Coronavirus Conversations.

This page is collecting analysis and reports from around the internet on the impact of Covid-19 policies in India. It even has a daily newsletter. The International Monetary Fund also has a big page of policy responses to the virus from around the world. And the Centre for Economic Policy Research is keeping track of the economic fallout globally.

The Coronathon for India is an IT community-created hackathon that is attempting to bring in ideas for how technology and the tech community can play a role in taking on the Coronavirus challenge.

And finally “India Covid-19 Tracker” is a very convenient, crowd-sourced webpage collecting all the data on cases, demographics and more.

Am I missing important analysis or portals tracking policy responses to Covid-19? Please send all suggestions to rohan@scroll.in

Can’t make this up

Rest of the world – and Indian doctors: We’re running out of personal protective equipment, which we desperately need.

Pharmacists in rich Indian neighborhoods (where maids, cooks and guards are expected to continue working and are then blamed for spreading the Coronavirus):

If you found the Political Fix useful, please do share and subscribe. And if we missed any useful links or tweets, write to rohan@scroll.in