The Political Fix: What does India's democratic backsliding mean for the Quad?

Plus, Covid-19 updates.

Welcome to The Political Fix by Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, a newsletter on Indian politics and policy. To get it in your inbox every week, sign up here.

We don’t charge for this newsletter, but if you would like to support us consider contributing to the Scroll Reporting Fund or, if you’re not in India, subscribing to Scroll+.

The Big Story: Odd man out

Will India’s illiberal turn under Prime Minister Narendra Modi hurt the country’s chances of engaging with the West?

We asked this question on the Political Fix six months ago:

“The challenge of living in a state that has moved away from pluralism as its stated aim is one that Indians will have to grapple with. Over the last few months, this drift has also led to a debate among those who follow India’s strategic thinking and foreign policy efforts…

American scholar Ashley Tellis kicked off last week’s round of the debate, arguing that “the community of liberal democracies internationally stands to lose if domestic unrest fueled by confrontational politics stymies India’s growth or if India enlarges its material capabilities only by sacrificing its liberal character. Either outcome would dilute the West’s eagerness to partner with India.”

…Still, knowing that the West has often been more than happy to work with despots and dictators though, will India’s recent moves actually harm its chances?”

The last few weeks have seen the West, or at least its public sphere, become much more cognizant of the democratic backsliding under Modi.

US-based non-profit Freedom House in its annual report downgraded the country from ‘free’ to ‘partly free’, saying “rather than serving as a champion of democratic practice and a counterweight to authoritarian influence from countries such as China, Modi and his party are tragically driving India itself toward authoritarianism.”

Sweden’s V-Dem Institute went a step further, saying “the world’s largest democracy has turned into an electoral autocracy.”

This led to a burst of coverage of developments in India, with the BBC examining the question of this ‘democratic downgrade’ and the Washington Post carrying a piece titled, “India, the world’s largest democracy, is now powered by a cult of personality.”

While for some, terms like ‘electoral autocracy’ or ‘partly free’ conjure up images of rigged elections and widespread political violence, Milan Vaishnav, director of Carnegie South Asia, explained in Foreign Affairs that,

“India’s drop in the democracy league tables has less to do with the nature of its elections—which are largely free and fair—than with the shrinking democratic space between them… These grim assessments point to several troubling political developments in the country: the consolidation of a Hindu-majoritarian brand of politics, the excessive concentration of power in the hands of the executive, and the clampdown on political dissent and on the media.”

The Indian government naturally pushed back against these assessments, citing both a genuine grouse about wayward and inconsistent Western readings of the country as well as less grounded claims of some sort of anti-India agenda from these organisations.

Treating all criticism, whether it comes from Indians or foreigners, as agenda-driven efforts from enemies of the nation are of course one of the indicators of the Indian government’s illiberal turn.

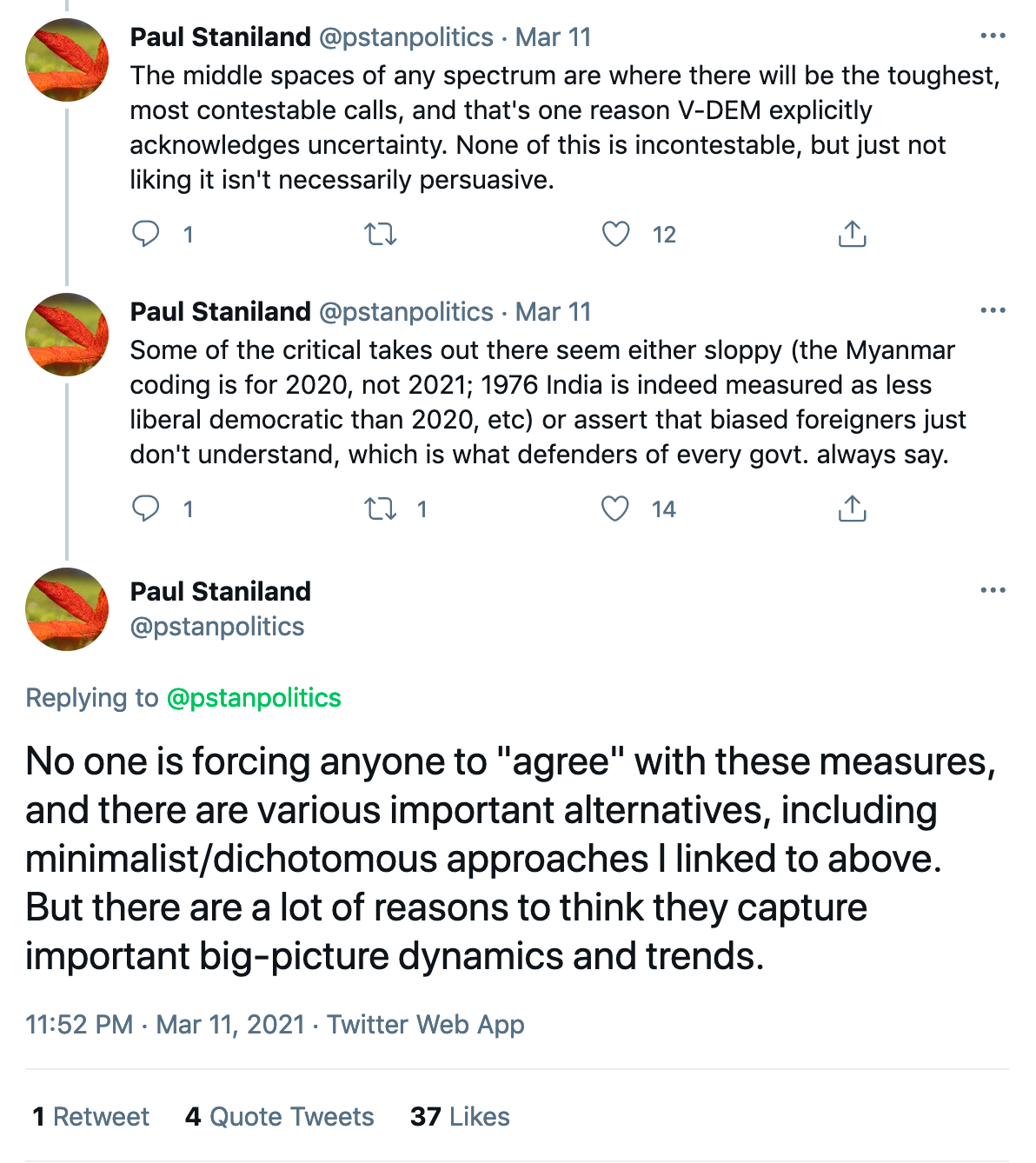

Political scientist Paul Staniland looked at V-Dem’s earlier assessments of India to see if charges of bias against the Bharatiya Janata Party were accurate in an insightful thread:

While Twitter debated these things, in the country itself the question of whether India had become less free seemed, quite literally, academic:

“Pratap Bhanu Mehta, a vocal critic of the Narendra Modi government, had resigned as professor of the Ashoka University on Tuesday, less than two years after he stepped down as the university’s vice chancellor. The university had refused to say whether his writings and criticism were connected to the resignation. Economist Arvind Subramanian also quit after Mehta’s exit…

In his resignation letter to Ashoka University, political scientist Pratap Bhanu Mehta said he was quitting because it had become “abundantly clear” to him that his association with the university may be considered a “political liability”.

“My public writing in support of a politics that tries to honour constitutional values of freedom and equal respect for all citizens, is perceived to carry risks for the university,” Mehta wrote. “It is clear it is time for me to leave Ashoka.”

Mehta, who is very well known in academic and intellectual circles, had in his regular columns for the Indian Express been writing about Modi and the BJP’s impact, with a recent piece titled “the real darkness on horizon is the turn Indian democracy is taking.”

Though some have questioned Mehta’s own analysis of Modi in the past and others have asked why developments at an expensive, private university have garnered more attention than the steady attacks on academic freedoms at public ones, the news undoubtedly added to the international impression of speech being threatened in India.

Political scientist Suhas Palshikar, who looked recently at questions of how to define India under the BJP, decided to read the tea leaves:

“The recent negative reports about India’s democracy have given a convenient handle to pseudo-intellectuals of the regime to commence this offensive of redefinition.

A time will come when it will be argued that democracy is a western notion unnecessary for true and spiritual emancipation — moksha. It will be claimed that there is an indigenous meaning to democracy. Liberalism and individual rights are a western fashion, institutional autonomy is a fetish, freedom of expression is a superfluous luxury (and of course, no freedom is absolute)…

The simplistic binary between electoral and non-electoral needs to be set aside. Regimes which initially hide behind the democratic fig-leaf often overemphasise the virtue of electoral victories and the will of the people…

The moment individual citizens or minorities and marginalised sections are silenced into self-censorship born out of the lure of social approbation or risk of repression, democracy based on the claims of so many votes begins to resemble its opposite.

Whether or not to call that opposite of democracy by the name of autocracy, authoritarianism, or partial freedom, is less important because non-democracy, by any name, will smell as odious — it will crush the “people” in whose name it has enthroned itself.”

So, will all of this hurt India’s chances of engaging with the West?

As of this week, self-evidently not.

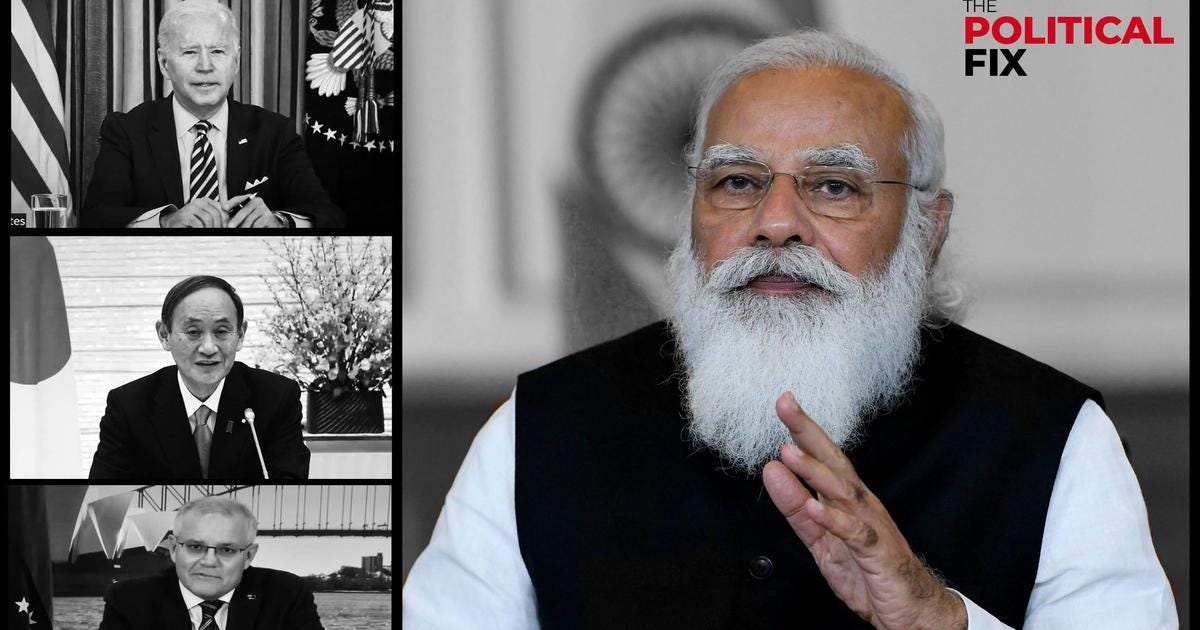

Modi joined US President Joe Biden, Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suge and Australian Prime Minister Scott Morrison in the first-ever leadership meeting of the ‘Quad’, a group of countries that has come together to support “a shared vision for an Indo-Pacific region that is free, open, resilient and inclusive.”

For nearly two decades now the four countries have coordinated on a few shared activities and discussed cooperating on many more. The grouping has also been seen, accurately, as an effort to contain China, as its influence in the region grows.

In last week’s summit, however, the leaders sought to convey the impression that the group aims to do much more than just counter Beijing militarily.

In an Op-Ed jointly written by the four leaders, the story of the Quad begins with the countries putting together a joint response to the Indian Ocean tsunami in 2004. Among the biggest agreements from the first summit was a decision to have India manufacture the Johnson & Johnson single-shot Covid-19 vaccine, with financing from the US and Japan and logistical support from Australia to distribute the vaccines across South-East Asia and Pacific countries. The gathering also saw added commitment to work together on things like climate change and critical technology.

Still, as Indrani Bagchi writes, “there’s no doubt a resurgent, aggressive and hegemonistic China is the wind beneath the Quad’s wings… The Quad’s the thin end of the wedge in what promises to become an expanding “toolkit” of a massive counterbalancing exercise.”

We’ll have more coverage and links to outcomes from last week’s Quad summit and further developments in the coming days.

But to return to the question, how does Indian democratic backsliding play into all of this? After all, in the joint Op-Ed, the four leaders wrote that “our foundations of democracy and a commitment to engagement unite us.”

Just a few days later, US Defence Secretary General Lloyd Austin III visited New Delhi, to meet Modi, Defence Minister Rajnath Singh and External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar. The meetings led to a number of major agreements, such an enhanced Indian cooperation with a number of US military commands – as opposed to just the Hawaii-based Indo-Pacific one – and collaboration on information sharing, artificial intelligence, space and cyber.

Among the things Austin brought up were questions of human rights abuses, which he had been urged to bring up by the chairperson of the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. Austin said he spoke to members of the Indian Cabinet about violations of human rights of Muslims in Assam, among other things, adding “India is our partner and a partner that – whose partnership we value. And I think partners need to be able to have those kinds of discussions.”

The Indian government, however, claimed this didn’t happen via anonymous sources:

As many expected, under US President Joe Biden, questions about human rights and liberal values are indeed more likely to come up, in ways that will be embarrassing for the Indian government under Modi.

Whether that will prevent the two countries from collaborating is a different matter altogether. One explanation for why it would matter came from the Hudson Institute’s Aparna Pande in a Friday Q&A last year, pointing out that India’s democratic reputation is a reason for its seat at the table:

“If India was growing at 8%-10% economic growth, if India had the military, which could stand up to China, then maybe we could turn around and say, you know, ‘Why are you [criticising our move away from liberalism]?

But actually we seem to have it bad on all fronts. Economic growth has slowed down. We haven’t invested in human capital as Covid shows us right now. Our military modernisation has not gone as planned. And we have political and social tensions… What is India offering aside from its image?”

What is India offering aside from its image? The answer might be quite simple: A willingness to take on China.

If, as the other Quad countries have concluded, that competition with Beijing will be the defining geopolitical contest of the decade, some amount of Indian democratic backsliding could well be ignored by the West as long as New Delhi stays firm on China.

Flotsam & Jetsam

The second Covid-19 wave has reached India. Cases are rising precipitously, particularly in Maharashtra where new case numbers are higher than in 2020. This has led to lockdowns and curfews in some cities, and warnings that more may follow.

While India’s vaccination efforts are reaching 2 million people a day, far ahead of many richer nations, the size of the population and the current pace means it will be a long time before a significant proportion gets immunity that way.

We’ll have links to stories from the states with assembly elections and the dramatic developments in Maharashtra on the Friday Links edition.

Can’t make this up

In both West Bengal and Kerala, several people have found their names on the Bharatiya Janata Party candidate lists without asking to be on there – or in some cases not even being members of the party.

This untranslatable interview is the outcome of those developments:

Thanks for reading the Political Fix. We’ll be back on Friday with a Q&A and links to pieces from around the web. Send feedback to rohan@scroll.in.