The Political Fix: Was Delhi the last of the BJP’s losses in state elections for the next few years?

A weekly newsletter on Indian policy and politics from Scroll.in.

Welcome to the Political Fix by Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, a weekly newsletter on Indian politics and policy. To get it in your inbox every Monday, sign up here.

If you expect spine, not spin from journalism, consider supporting us either by subscribing to Scroll+ or contributing to the Scroll.in Reporting Fund.

Today’s newsletter is a bit truncated, since I’m away for some of the week. We’re only looking back at Delhi elections and will be back to regular programming with headlines, recommendations and links next week.

If you have a specific recommendation or actually prefer this shorter format, please write in to rohan@scroll.in.

The Big Story: Speedbumps

If you looked only at state election results from India over the last few years, you might think that the Bharatiya Janata Party – which is in power at the national level – is in a difficult position.

This week, the BJP led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Home Minister Amit Shah received an absolute drubbing in Delhi Assembly elections, winning just 8 out of 70 seats, with all the rest going to the incumbent Aam Aadmi Party.

Indeed, since late 2017, the BJP has had a very middling record at the state level, something we mentioned in our 2019 round-up and looked at more closely in a previous edition of the newsletter.

Uttar Pradesh, May 2017: Huge win for BJP.

Gujarat, December 2017: Narrow win for BJP.

Karnataka, May 2018: BJP is the single-largest party, but initially can’t form the government.

Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, December 2018: BJP loses all three states to Congress.

Haryana, Maharashtra, October 2019: BJP needs JJP’s support to form government in Haryana, loses Maharashtra to a grand coalition including former partner Shiv Sena.

Jharkhand, December 2019: BJP loses the state to a JMM-Congress coalition.

Delhi, February 2019: BJP receives a drubbing at the hands of incumbent AAP.

Right in the middle of this line up, in May 2019, were India’s last general elections, in which the BJP managed a massive victory, winning a second Parliamentary majority with more seats than it did in 2014. But it has not been able to turn that massive national dominance into equivalent success in the states.

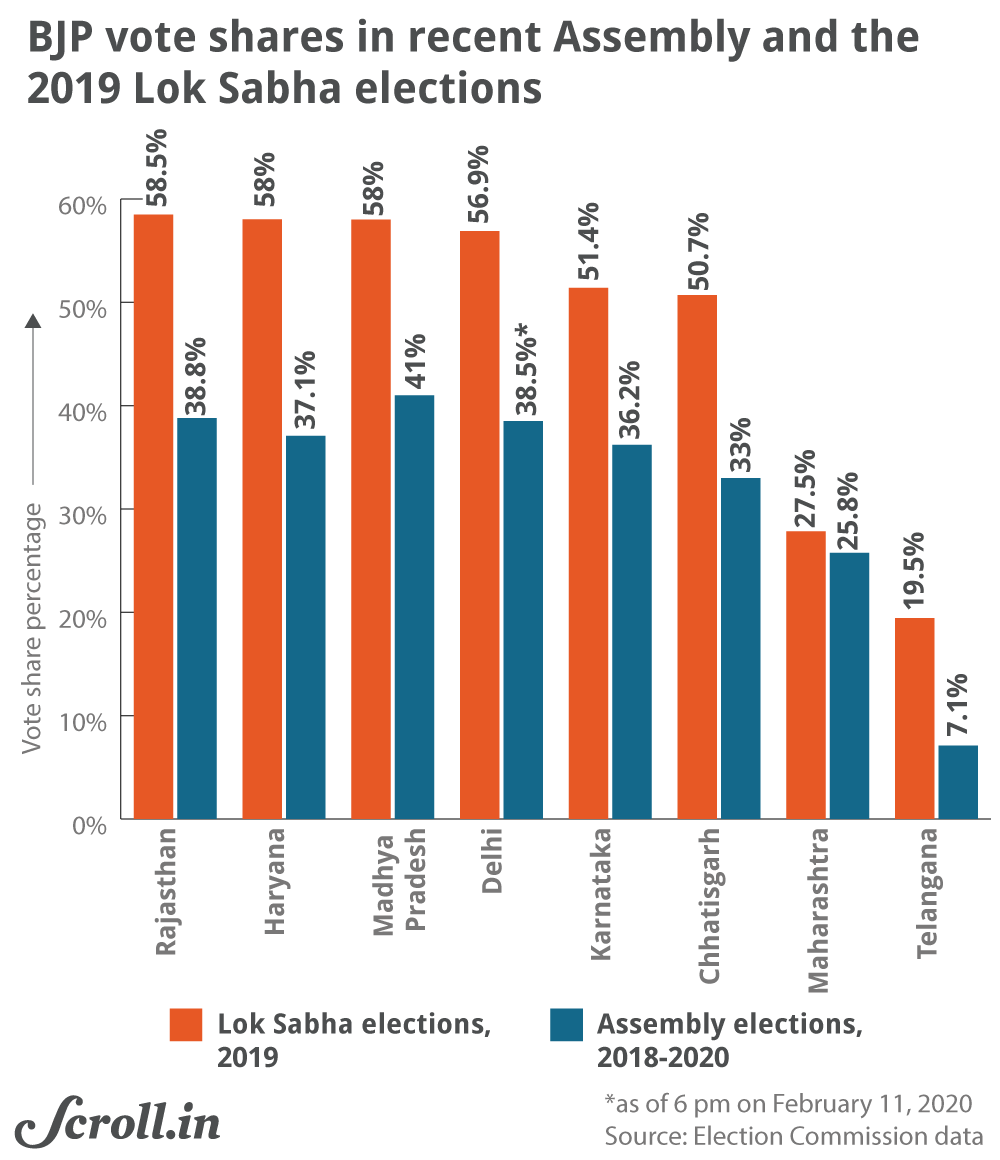

In many states there is more than a 10 percentage point difference between the vote share the BJP was able to pick up in the general elections in May 2019 and the percentage it garnered in state assembly elections over the last three years.

My colleague, Shoaib Daniyal, examined this issue soon after the Delhi results were announced.

“The BJP’s planks of muscular nationalism and majoritarian identity won it a handsome victory at the national elections in 2019. But when it comes to state assemblies, voters seem to prioritise more prosaic issues of welfare benefits and livelihood. This has resulted in the BJP in 2020 controlling the smallest number of states for any party that has a majority in the Lok Sabha in India’s history.”

Add in the Great Indian Slowdown that has seen Gross Domestic Product growth numbers fall significantly, and the sustained large-scale protests against the government taking place around the country, the BJP seems like it is on the back foot despite its Parliamentary victory a year ago.

But what if this is the worst of it for the BJP?

Let’s look at the election calendar for major states up ahead:

Bihar, around October 2020

Assam, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, West Bengal, around May 2021

Uttar Pradesh, Punjab, around March 2022

Gujarat, around December 2022

As things stand right now, the BJP is the front-runner in Bihar (with the Janata Dal United), Assam (despite the Citizenship Act protests), Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat – all states it currently controls. Punjab is more complicated, though any success there would likely depend more on the status of its senior alliance partner, the Shiromani Akali Dal.

It is a bit player in Kerala and Tamil Nadu, despite efforts to increase its presence in both states.

The only major question is West Bengal, which has been in the BJP’s crosshairs for the last few years and may even be partly responsible for its insistence on pushing the controversial Citizenship Act amendments.

But the BJP has only just built up a significant presence in West Bengal, winning a surprising number of Parliamentary seats in last year’s national elections. So a failure to win power would be a missed opportunity, not a catastrophe for the party.

As it stands, then, the BJP might be past the worst of the state results – with another four years of Parliamentary control ahead.

Let me just add two caveats:

Just because the calendar looks favourable to the BJP doesn’t mean it will be. Few people predicted that the party would lose control of Maharashtra and need to form an alliance to remain in power in Haryana. Political fortunes can change quickly and Bihar, Assam or even UP could throw up a surprise.

Elections are only a part of the picture. At least three other developing stories could hurt the government’s narrative even without electoral setbacks: The economy could continue its downward slide even as food prices rise further. Anti-Citizenship Act amendment protests might grow even larger, drawing in other causes. Global condemnation over the government’s controversial actions in Kashmir and on the Citizenship Act front might grow louder. And of course, that is not accounting for unforeseen shocks.

Delhi Election Watch

The Delhi elections are done and dusted, and mostly went as expected: A huge win for the Aam Aadmi Party, despite last-minute efforts by the BJP to polarise the public on religious lines. For background, read our preview of this election from a few weeks ago.

As results were still coming in, I offered a few quick takeaways, discussing briefly the growing stature of AAP founder Arvind Kejriwal, the complete disappearance of the Congress from Delhi and the BJP’s state unit difficulties.

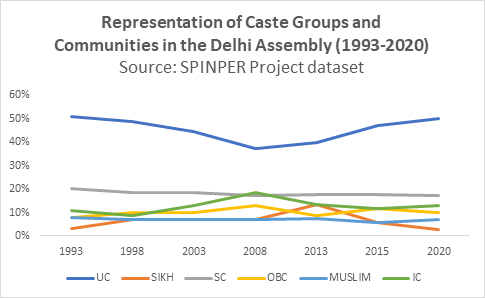

Gilles Verniers and his team at the Trivedi Centre for Political Data put together 30 maps to help understand AAP’s post-identity politics.

“The case of AAP is both interesting and revealing, as this is a party that claims to be blind to caste differences. Yet, it provides preferential representation to traditional and elites to a large extent: Brahmins and Banias. Non-traditional business elites like Jats and Gujjars also find good representation in AAP. In this assembly, nearly half of AAP’s 62 MLAs are upper caste and half of them are Brahmins. This does not happen by coincidence.”

I wrote two more pieces on these results.

The first concerns AAP’s Delhi model and what Kejriwal might do with his success. He has always had national ambitions and even worked with well-connected political analyst Prashant Kishor this time. Could he take another shot at going beyond Delhi? Or will another politician from a bigger state try and emulate the Delhi welfare model?

The other looks at a common point of debate in the aftermath of AAP’s big win.

Kejriwal did not take on the BJP’s ideology directly in his campaign. Instead, he focused on welfare and development and drew in many voters who chose Modi at the national level a year before.

Does that mean that, despite BJP’s defeat, its right-wing Hindu nationalist ideology still won? Or is Kejriwal’s non-confrontational approach a smarter way of winning the debate?

Law and order in Delhi is controlled by the Union Government led by the BJP, so even if AAP wanted to do more, it would have been hamstrung. Instead it kept its talking points simple – governance and welfare – and focused on getting to the date of voting without falling into the BJP’s rhetorical traps.

At a time when being in charge of a state might be the most powerful way to push back against the Hindutva ideology built into the Citizenship Act amendments, this focus on winning votes and not the rhetorical argument need not be considered cynical.

Thank you for reading. If you enjoyed the newsletter, please do share it! We’ll be back to the regular format next week – please write in with any suggestions, angry comments or funny memes: rohan@scroll.in

Great analysis as usual. I also think that the resounding vote share of BJP at national level is due to lack of an alternative, and not just the muscular hindutva appeal (that many commentators are identifying as the main cause).

At state levels, mostly when a viable alternative was presented, BJP has had a tough time. The hindutva ideology appeal starts to dissipate as one moves away from the cow belt states (UP & Bihar mainly).