The Political Fix: India enters its 75th year with a climate warning – and a battle over 'net zero'

A newsletter on politics and policy from Scroll.in

Welcome to The Political Fix by Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, a newsletter on Indian politics and policy. To get it in your inbox every week, sign up here.

Our small team wants to cover the big issues. That is why we are appealing for contributions to our Ground Reporting Fund. If you’d like to assist our effort, click here.

The Big Story: Neti neti

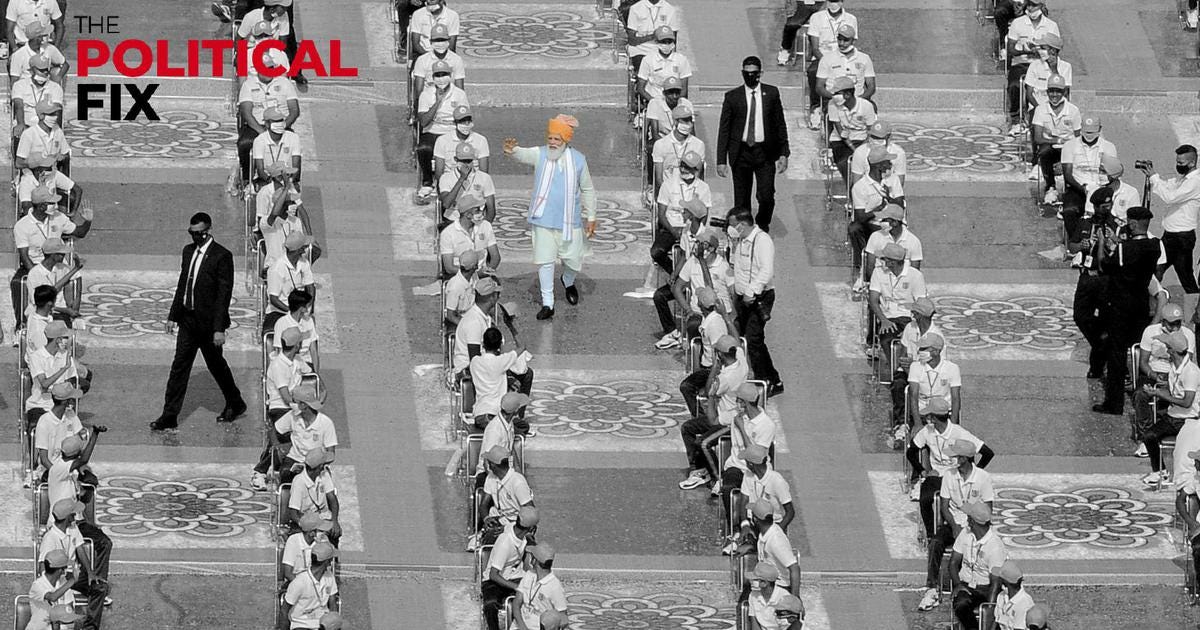

India kicked off its 75th year celebrations on Sunday, with Prime Minister Narendra Modi – in his annual Independence Day address from the Red Fort in Delhi – calling for the country’s transformation over the next 25 years.

Aside from announcing some relatively minor new initiatives and making little mention of the horrors of India’s disastrous Covid-19 second wave earlier this year, Modi also added a new element to his now-unwieldy slogan that was originally and misleadingly meant to assuage fears of majoritarian politics: Sabka saath, sabka vikas, sabka vishwas – and now sabka prayas. (All together, everyone’s development, everyone’s trust – and now everyone’s efforts).

As the country geared up for what is likely to be a year full of debates about the past, evaluations of how far it has come and questions about the trajectory India is taking – see Pratap Bhanu Mehta and Mukul Kesavan – one warning shot about the future was sounded in the week before Independence Day.

My colleague Ishan Kukreti writes,

“Threat assessment, level 6.

Two years before the world converged in Rio De Janeiro in 1992 to seriously discuss climate change and long before Marvel and DC turned into cinematic universes, there was a green-haired superhero trying to save the world from environmental problems on Cartoon Network.

Almost 30 years since, those who thought the agenda of Captain Planet was overly paranoid and unnecessarily preachy, may be in for a shock. The latest report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change is nothing less than a big “I told you so” by the Planeteers.

IPCC is a consensus building body on the science around climate change. What this means is that the body reviews the latest scientific evidence (this time over 14,000 studies) and categories them on their level of certainty as High Confidence, Medium Confidence and Low Confidence.

The latest report, Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis by the Working Group I of the Assessment Report 6 of IPCC, has more High Confidence categorisations than the previous Assessment Report 5 released in 2013. Things can’t be going well when a group of 234 scientists unanimously vouch, with high confidence, that humans have all but broken the planet.

This IPCC report is the sixth attempt by the world to look at the beast of climate change directly in the face and calibrate how dangerous it is.

So how is different from the last assesment in 2015?

For one, the scientists are much more confident that it is human activity which is causing climate change. The last assessment had around three such attribution studies, while this time around there are more than 100.

The report says that even if the world spewed the least amount of carbon dioxide (a situation which the report categorises as a low Greenhouse Gas emissions scenario), chances are that the planet will still get hotter by 1.5°C compared to 1850-1900 temperature levels, within the 21st century. Keeping global warming limited to 1.5°C was one of the more ambitious goals of the big Paris Agreement of 2015. In the worst-case scenario, the temperatures could rise as much as 3.3°C to 5.7°C.

Why do these estimations matter? Because global warming amplifies the change in climate and its impact. So increased warming, according to the report, would mean, “increases in the frequency and intensity of hot extremes, marine heatwaves, and heavy precipitation, agricultural and ecological droughts in some regions, and proportion of intense tropical cyclones, as well as reductions in Arctic sea ice, snow cover and permafrost.”

The report also points to a Catch-22 situation. As much as 0.5°C warming has been prevented by sulphates, mostly emitted from the chimneys of coal power plants, since the late 19th century. However, these sulphates contribute to air pollution, choking cities and killing its inhalers.In India, the Global Burden of Disease, published by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, estimates 1.67 million deaths due to air pollution in 2019.

Now, with all major air polluted cities bringing in legislation to bring these sulphates levels down, as with the Commission for Air Quality Management in National Capital Region and Adjoining Areas passed by the Parliament on July 30, an unintended consequence of it will be an increase in warming. The report suggests offsetting this by limiting methane emissions. Methane has a higher warming potential than carbon dioxide, but does not remain in the atmosphere for as long.

The report estimates, with medium confidence, that heatwaves will be more intense and frequent during the 21st century in the South Asian region and both annual and summer monsoon precipitation will increase during the 21st century. The Indian monsoon has been a battleground, so to speak, between the changes brought in by carbon emissions and those by aerosol emissions.

Aerosols are suspended particles in the atmosphere and are created by air pollution sources like vehicular and industrial emissions. The report says that it is these pollution-created particles which have led to a reduction in the Indian monsoon in the second half of the 20th century. But it estimates that in a high GHG emissions scenario, the effects of carbon emissions will overtake those of aerosols and lead to an increase in monsoon rainfall in India.

In its response to the report, the Indian environment minister, Bhupendra Yadav, pointed to the higher per capita emissions of developed countries since the last 19th century and called the report a "clarion call" for the developed to make immediate emissions cuts.

However, the report's finding of a wetter monson in the future along with the experience of the recent floods in the Western Ghats, it seems the monsoon question is on the Indian environment ministry's radar, which, in a statement released on August 9 said, “the report brings out that the monsoon rainfall is expected to intensify in all ranges of the projected scenarios. Intensity and frequency of heavy rainfall events are projected to be on the rise. India notes that the rising temperature will lead to increased frequency and intensity of extreme events including heat waves and heavy rainfall.”

This report is the first of the three reports which will form the Assessment Report 6. The report of Working Group II (impacts, adaptation and vulnerability) and Working Group III (mitigation) and a Synthesis Report will be released by September 2022.

For the common man this report might not be more than an exercise in improving statistical exactitude by adding a degree here or a millimetre there, but it will be the ammunition that government negotiators take to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change Conference of Parties to be held later this year in Glasgow. Carbon finance, markets mechanisms, adaptation funds and new and improved nationally determined contributions will be some of the topics to be haggled over.

So, it might be that you never liked the preachy sermons of Captain Planet, but you can be certain that the Earth’s greatest champion was telling more truth than his Cartoon Network compatriots.”

Among the various takeaways from the report were what it said about climate change’s impact on the Himalayas, on the water cycle, on India’s cities and on the likelihood of extreme weather events.

One immediate impact, though, may be on India’s negotiating stance ahead of COP26, the big climate change conference slated to take place in Glasgow in November. The IPCC’s report “is likely to translate into increased pressure to agree to a net-zero target, a deadline by which it should be able to bring down its emissions to a level that equals the absorptions made by its carbon sinks, like forests.”

Net-zero is a complex concept, that may seem appealing on paper but would be much harder to implement on the ground, particularly in emerging nations like India. As Lou del Bello wrote earlier this year, “the goal comes with harsh trade-offs for any country that has committed to it, but India's unique combination of its size, population still living in poverty and fast paced growth means that modellers who try to demonstrate such a drastic decarbonisation is possible raise more questions than they answer.”

More than a hundred countries the world over, including major emitters like the United States, the European Union and China, have announced plans to achieve net-zero emissions targets by the middle of the 21st century. India is one of the most significant hold-outs.

Earlier this year, it seemed as if New Delhi might be persuaded to join the net-zero club. But over the last few months, India has hardened its stance and stayed away from multilateral meetings where many expected pressure to toe the global line.

Instead, New Delhi plans to argue – as it did at the G20 meeting earlier this year – that the responsibility falls on historical emitters, which ought to be cutting their emissions faster in order to leave carbon space for developing countries to grow.

In his Independence Day speech, Modi claimed India was the only one of the G20 nations to make significant progress towards its climate change commitments, and listed out an ambitious set of targets to make the country energy independent by 2047 – albeit without acknowledging how far away it is from achieving previous targets on things like solar power generation by 2022.

COP26 President and British Member of Parliament Alok Sharma is visiting New Delhi this week, in part to prepare the ground for the big conference later this year. Sharma will be meeting Environment Minister Bhupender Yadav, who has made clear where India stands on the ‘net-zero’ quersion for now, and what it is likely to say over the next few months.

Linking Out

The unravelling of a conspiracy: were the 16 charged with plotting to kill India’s prime minister framed? By Siddhartha Deb.

As the Taliban completed a stunning takeover of Kabul that came quicker than even the most pessimistic projections, Indian policymakers were left contemplating how to move forward. Suhasini Haidar list out four options for New Delhi.

Union Commerce and Industry Minister Piyush Goyal delivered an unexpected, unprovoked 19-minute tirade against the business practices of Indian companies, including directly attacking the Tata Group.

“Parliament appears to be quite ineffective in all its functions... This session, the Government got every Bill that it introduced passed as an Act, without any debate, and without any scrutiny by committees. Question Hour hardly worked. There was just one debate in the Rajya Sabha and none in the Lok Sabha on policy issues,” writes MR Madhavan.

“There is now widespread agreement that the monetary-policy option has run its course, even while there is disagreement about whether this is an opportune moment for RBI to actually begin withdrawing its extraordinary monetary support to the economy,” writes Niranjan Rajadhyaksha. “The economic impact of the pandemic has expectedly moved from its first stage as a supply shock to its second stage as weakness in domestic aggregate demand.”

Malavika Kaur Makol and Anirban Nag explain how inflation is hurting Indian companies, which may be passing the pain on to consumer soon.

Roshan Kishore asks if targeted welfare efforts from the government can override inflation concerns.

Can’t make this up

If there were awards for saying something with a straight face...

Thank you for reading the Political Fix. Send feedback to rohan@scroll.in.

Support our journalism by contributing to Scroll Ground Reporting Fund. We welcome your comments at letters@scroll.in.