The Political Fix: How will Narendra Modi’s pandemic politics change as India enters Lockdown 3.0?

A weekly newsletter on Indian policy and politics from Scroll.in.

Welcome to the Political Fix by Rohan Venkataramakrishnan, a weekly newsletter on Indian politics and policy. To get it in your inbox every Monday, sign up here .

Before you go any further, I have a request. Journalism in these testing times needs your support. To ensure that our reporters can dig deeper and go further, you can us either by subscribing to Scroll+ or by contributing as little or as much as you would like to the Scroll.in Reporting Fund.

One more thing: Last week’s The Political Fix was the last one to be illustrated by Nithya Subramanian, who has been a key part of this newsletter ever since it was called the Election Fix. You can look over all her illustrations for the newsletter here.

The Big Story: Disappearing act

Covid-19 cases in India: 40,263

Recovered: 10,885

Deaths: 1,306

India’s lockdown was announced by Prime Minister Narendra Modi in a primetime speech on March 24 in which he warned that if Indians did not stay indoors for the next 21 days, the country could be set back by 21 years.

When the three-week lockdown was at its end, Modi appeared on TV again – on the very last day – to inform citizens that they would have to remain locked down for two more weeks, and that he saluted them for all the suffering they were going through.

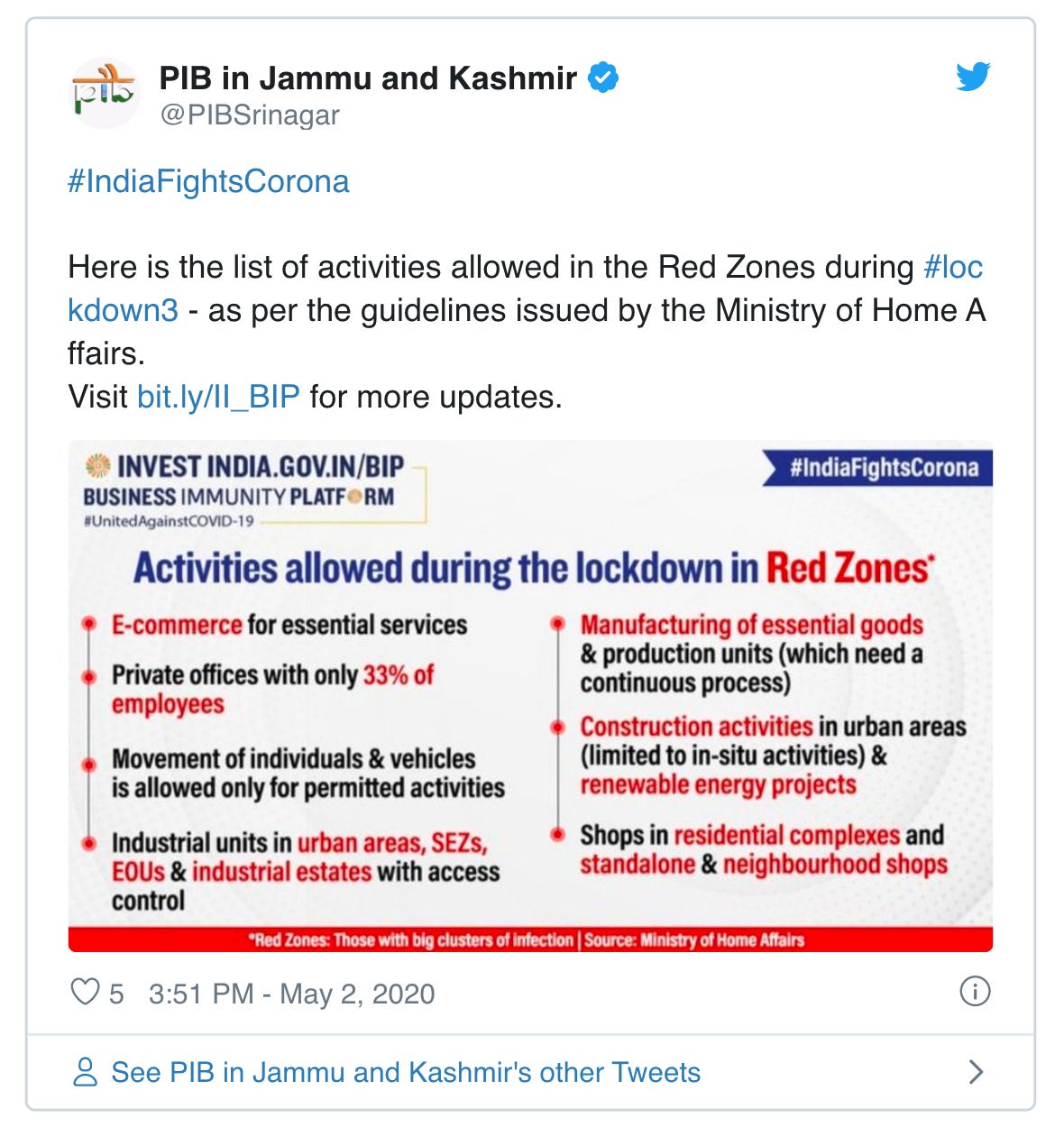

On Monday, India goes into the third-phase of its lockdown, this time until May 17, with considerable relaxations for various activities particularly in zones classified as green and orange, and even some easing up in red zones – other than containment zones. (Giving solace to many, this means that liquor shops will also be open in most places).

This time there was no Modi speech. Instead, the news was relayed through the Ministry of Home Affairs. Unlike the prime minister, the ministry did not wait until the last day of the lockdown, and instead put out documents with the various rules (followed soon after by the now-routine clarifications).

Modi may yet speak to the public about what lies ahead. Yet the change in communication strategy alone is significant.

One way of looking at it is that the prime minister has realised that his speeches have persuasive power but are rarely informative. Specific instructions, it’s clear, are better left to the bureaucrats or the state leaders who will have to tweak the national rules to their specific contexts.

After all, it was Modi’s failure to reassure the public in his first lockdown speech that forced him to tweet, “THERE IS NO NEED TO PANIC” right after.

An equally likely explanation, however, is that this approach fits in with Modi’s love of grand gestures, without an interest in getting into the nitty gritty. Lockdown 3.0, as it is being called, will be a complex affair, with different rules for different areas. Activity will return to large parts of India, even as the number of coronavirus cases and deaths continues to climb.

Moreover, the five weeks of lockdown have brought a migrant worker crisis, a massive rapid testing mess because of the Centre’s mismanagement and an economic and humanitarian disaster with little sense that Modi’s government has either a financial or welfare strategy in place to address any of this.

As we discussed earlier on the Political Fix, India locked down very early into the spread of Covid-19 – when there were only about 500 known cases in the country. India now has 40,000 cases, and the number continues to rise. India’s lockdown decision was quite unlike other places where the lockdown was used to flatten the curve.

Because of the rapid testing fiasco, India does not yet have the capabilities for widespread testing to gauge how much Covid-19 has spread in the population, a failure that could mean the lockdown was to some extent wasted.

As we have also examined, a crisis like this exposes the limits of state capacity. Modi’s moral authority can only keep people indoors, without work or food, for so long. Even though India’s health authorities may want to extend movement restrictions until more testing facilities are in place, and healthcare systems are better prepared, it seems unlikely that people will follow their call.

Is it any wonder then that Modi doesn’t want to be the one breaking the bad news to the people?

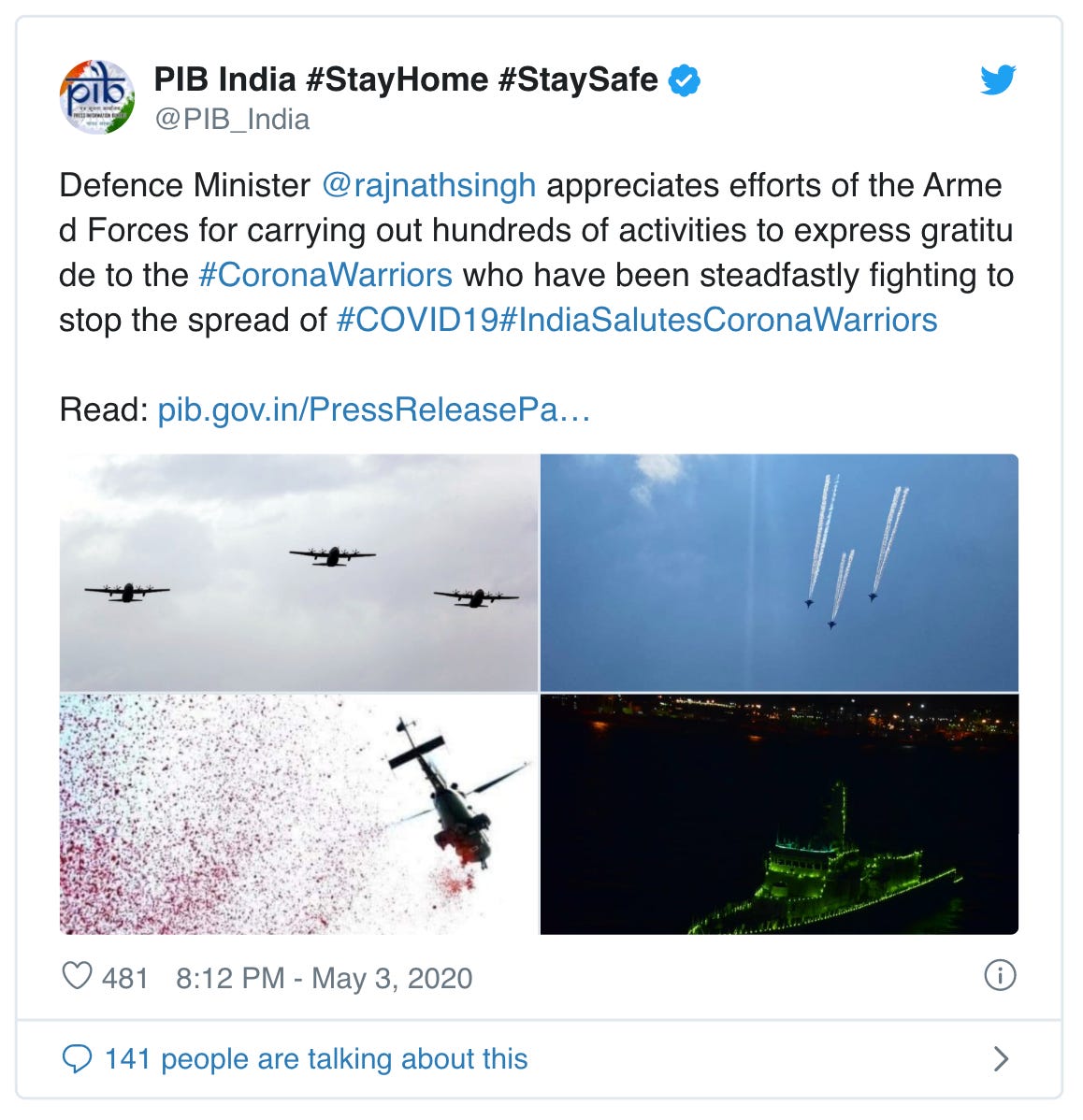

Instead, we get another classic Modi grand gesture borrowed from another country, this time announced by military leaders: fighter jets performing flypasts across the country, military bands playing for healthcare workers and helicopters dropping rose petals on hospitals.

This might explain why, despite government support failing to reach the poor, Modi’s approval numbers are soaring, just like they did after demonetisation. It may also explain why there is support for the lockdown even when there has been a significant loss of income across the board.

Pandemic politics

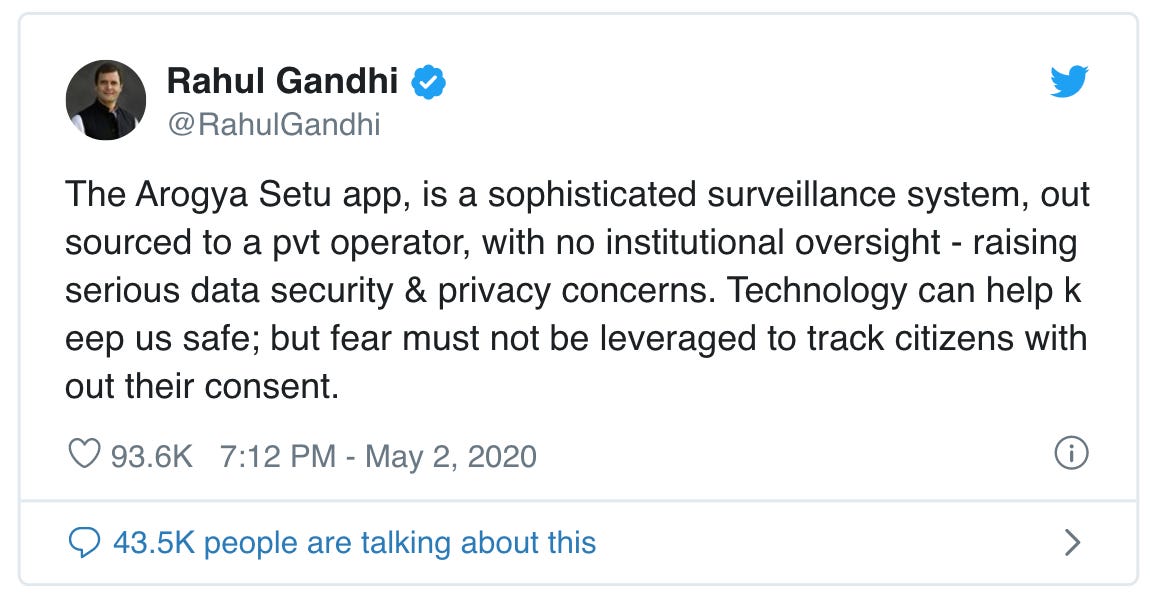

Former Congress President Rahul Gandhi tweeted last week about Aaryogya Setu, the government’s contact-tracing app that started out as a voluntary exercise but has quickly become mandatory for most people.

More about the app itself below.

But first, the arrival of this tweet – just at the end of Lockdown 2.0 – is interesting for a few other reasons.

It may end up being one of those issues that Rahul Gandhi takes up without getting much support either from his own party or the broader Opposition, like his questions about the Rafale deal.

But it also represents a more direct attack on the blueprint that the Centre has for its Covid-19 response than much of what we have seen over the last five weeks.

Sure, states have complained about the Centre’s botched handling of the migrant worker crisis and about its unwillingness to distribute funds. West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee has, as expected, been the most combative (with the Centre-appointed Governor playing Opposition leader, as Shoaib Daniyal points out).

But most of the back and forth has been quibbling about implementation, rather than asking fundamental questions about the need for a lockdown, the attitude towards the poor and migrants and a blueprint for handling Covid-19.

Among others, Carnegie’s Milan Vaishnav and Suyash Rai and the Centre for Policy Research’s Asim Ali and Ankita Barthwal wrote last week about the space wrested by the Bharatiya Janata Party to play its own politics (whether that involves deepening the Hindu-Muslim divide or arresting anyone critical of the government) even as most Opposition formations seem to be dormant.

Political scientist Suhas Palshikar was the first to warn about the effects a lockdown might have on India’s democracy. I spoke to him last week about this “suspension of politics” and what the future holds for India.

“If you had to project out by a couple of years, what does this change for Indian politics? What will be different in, say, two years time?

In the near future, very quickly it seems like that we’ll see both the collapse of the bureaucracy and the judiciary.

The collapse of the bureaucracy in a very different sense. This would be represented by actually more bureaucratic authoritarianism, and therefore collapse of the bureaucracy as an instrument of the government. And in the case of the judiciary, there would be a complete absence of any judicial protection of procedures.

Both put together, what one can imagine in the near future is a more strong popular contempt for procedures, and popular disinterest in legal protections.”

Bridge to nowhere

Countries around the world have turned to technology to solve the Covid-19 crisis. Contact tracing apps, which use location and bluetooth data to track who you have come into contact with, are among the most popular of these tech solutions.

Yet they have brought with them many questions about privacy and how the government intends to actually use the data.

The Indian government has settled on Aarogya Setu, which means “bridge to health”, as its weapon against the virus – since it obviously cannot lean on higher testing rates or health system preparedness. Home Ministry guidelines make it mandatory for everyone in containment zones and all employees, public and private.

This means it may soon be on the phones of hundreds of millions of people who have no choice to refuse it, regardless of whether they have concerns about the use of their data. And there ought to be concerns.

For context, it is always useful to remember that it was this very government that argued in the Supreme Court that Indians have no fundamental right to privacy, a position the court rejected. Aadhaar, the controversial 12-digit biometric identity project, started out as a voluntary effort but was expanded massively by this government with scant regard for privacy or rights.

We’ll be taking a closer look at the controversies around the app in coming issues. For now, read the joint representation from the Internet Freedom Foundation and 44 other organisations expressing solidarity against the mandatory use of Aarogya Setu.

Medianama also has a useful thread on the app:

You can check it out here.

Going home

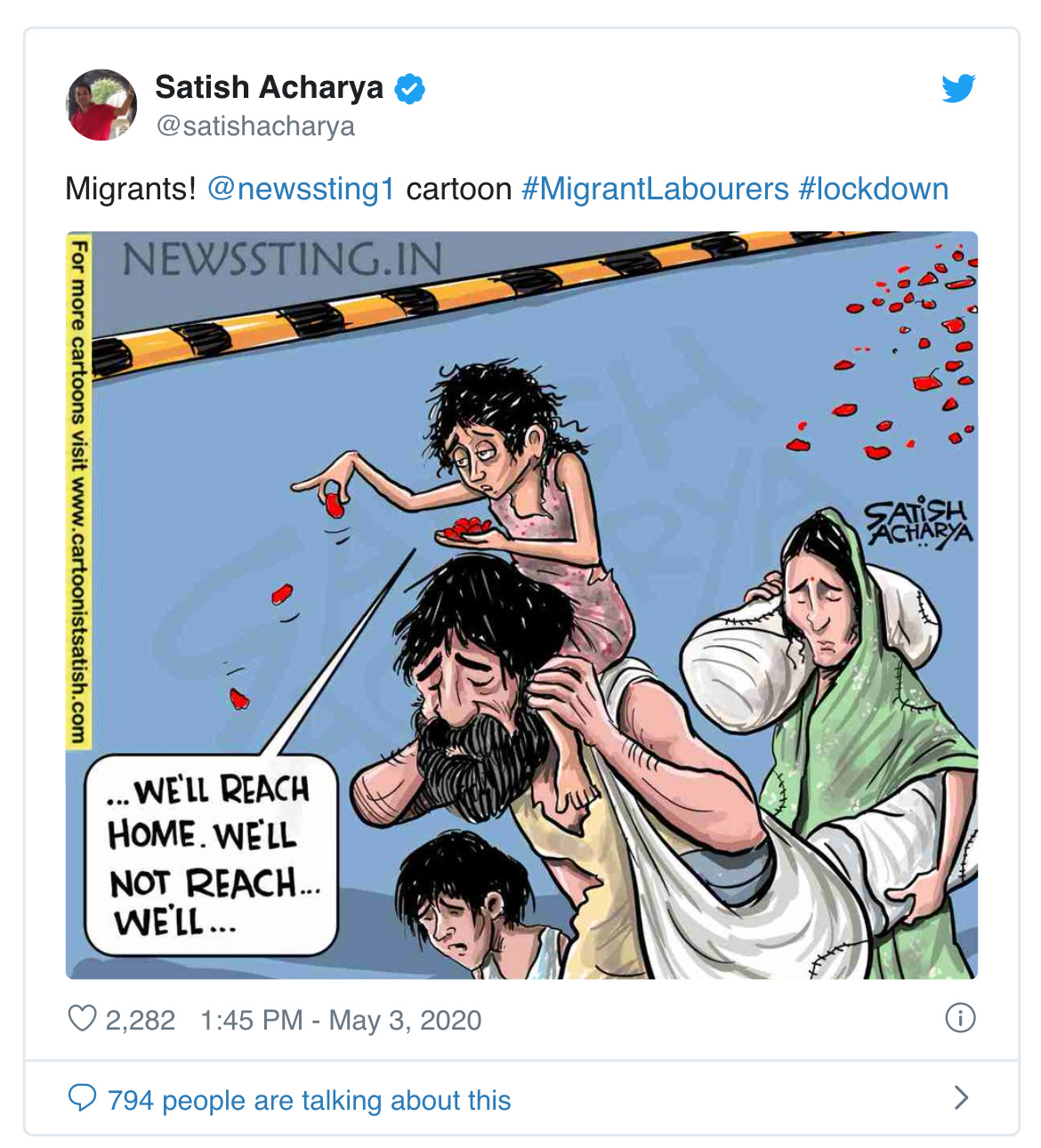

To yet again be reminded of the migrant worker crisis in India, watch this disturbing video of people hiding inside a cement mixer truck in the hopes of getting home despite the lockdown.

I broke down the complexity of the migrant worker crisis for policymaking a few weeks ago and the need for more humane decision-making, since it seemed like the government was treating migrants as resources rather than individuals with plans and desires.

Now five weeks after the lockdown was imposed, the government is finally allowing states to take migrant workers home, with no explanation for why it was prohibited earlier but allowed now.

However, after being forced to stay in shelters, with limited access to food andin many cases denied their due wages due, the migrants are now being asked to pay to go home – in some cases at higher rates because the occupancy of buses is limited due to social distancing norms.

Shoaib Daniyal writes here about how the Centre has the money to shower petals on hospitals, but not to pay for migrant workers to go home, even though inter-state travel is New Delhi’s responsibility.

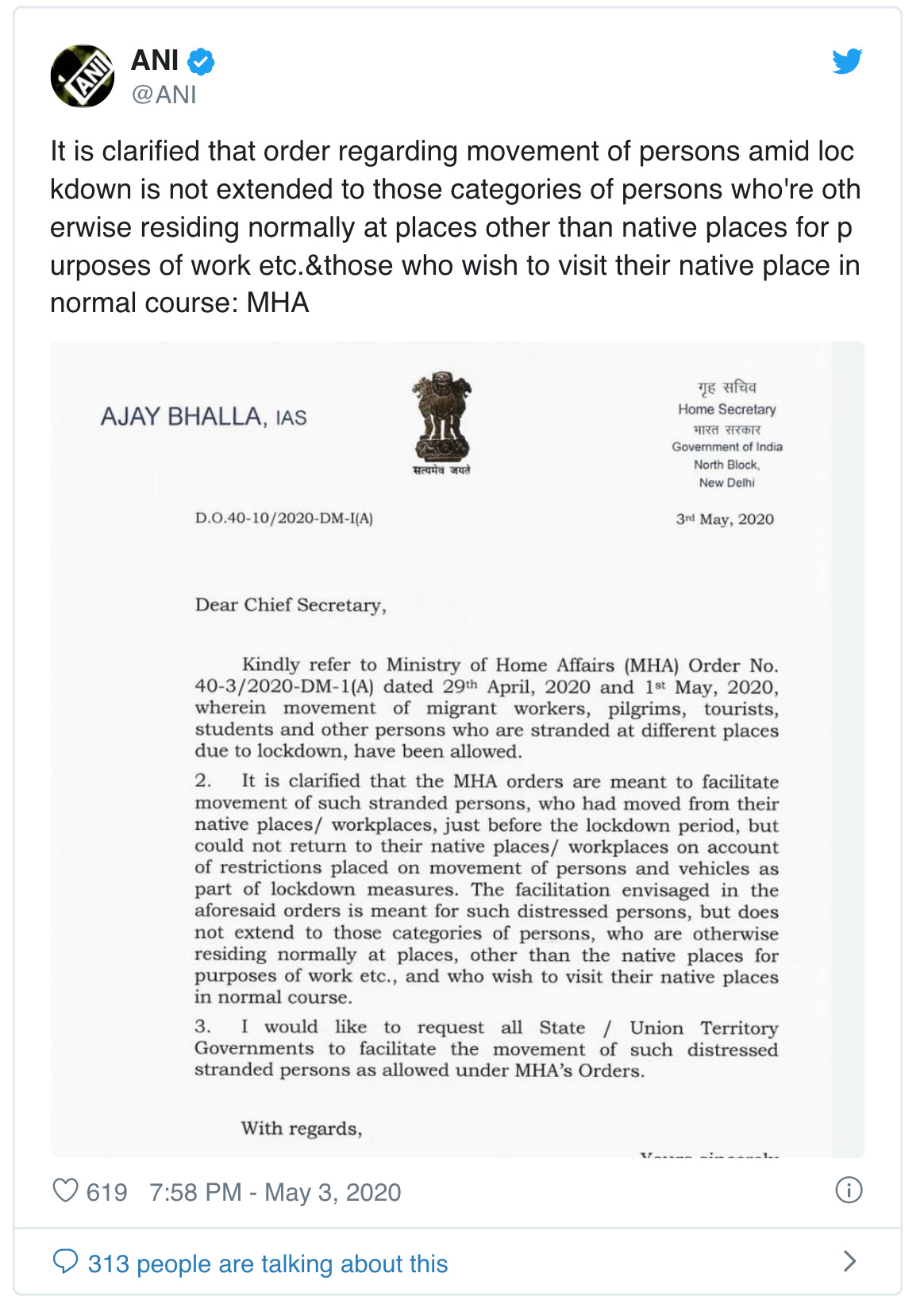

Late on Sunday another frill was added by the government: This inter-state travel was only permitted to those who had moved right before the lockdown and need to get back, not to seasonal migrants, adding confusion that has yet to be resolved. Meanwhile, states and political parties have been calling on the Centre to pay for the travel.

Flotsam and Jetsam

Five states have made it legal for employees to use 12-hour shifts for workers, rather than the standard 8-hour shifts. Gujarat and Himachal Pradesh are not even mandating double pay for the extra hours. Meanwhile, as business owners wait for a financial package from the government, they are bleeding. Plus, India’s ninth-largest mutual fund house wound up six of its debt funds – sending shockwaves around the mutual fund sector, as I explain here.

Though India’s mortality rate remains low, nearly 50% of those who have died are below the age of 60. Is India an outlier in terms of Covid-19 cases?

Unrelated to the virus, India lost film actors Irrfan and Rishi Kapoor, Delhi chronicler RV Smith and football star Chuni Goswami all this week.

Recommendation Corner

Srinivas Kodali is a researcher with a focus on data, governance and the internet. He also hosts Cyber Democracy, a podcast on the Suno India network.

Here are his recommendations:

“With a lot of talk around the failure of the free market to prepare for this global pandemic exposes its fragility, Noam Chomsky in his recent interview explained the cruelty of neo-liberal capitalism, using the example of a ventilator shortage.

But capitalism actually loves disasters.They helps to create a clean slate to capture markets and push new economic agendas. Naomi Klein has extensively documented this rise of disaster capitalism in her book The Shock Doctrine. This book is more relevant to us as the pandemic shows the cruelty of inequality in India.

Free-market advocates in India have already captured the welfare state by privatising parts of it using databases and systems like Aadhaar, Direct Benefit Transfer and IndiaStack for their business interests. While these systems may work, they also harm a section of population who are invisible to these systems.

Cathy O’ Neil explains these failure scenarios and how math/data can discriminate against people in her book Weapons of Math Destruction. In a recent column for Bloomberg, she explains how to look at the rise of contact tracing apps and how they won’t include the poor people.

The issue with the coronavirus is, if you ignore anyone based on their social status, religion or even sexuality due to the stigma of disease, the disease will continue to spread. Not caring for the poor is not an option the rich can afford.

A recent paper by Subhashis Banerjee and Subodh Sharma of IIT Delhi and Bhaskaran Raman of IIT Bombay titled Apps for COVID: to do or not to do, also tells us about the reliability of these contact tracing apps, while cautioning us to avoid techno-determinism.”

Have recommendations for an article, book, podcast or academic paper that deals with Indian politics or policy? Send them to rohan@scroll.in.

Previous recommendations from the Political Fix are collected here.

Ground Report

Supriya Sharma brings you a glimpse into the lives of those who were given no choice but to attempt to go home, 600 kilometres away, on cycles and empty stomachs.

If you value journalism that gets you the unvarnished truth, particularly in these momentous times, please do consider supporting Scroll.

You can contribute as little as Rs 500 (or as large a number as you would like to put down) to the Scroll Reporting Fund or subscribe to Scroll+ at a set rate every quarter or year.

Linking Out

Private hospitals have two-thirds of all beds in India. Yet they have less than 10% of critical Covid-19 patients. Prabha Raghavan, Tabassum Barnagarwala and Abantika Ghosh in the Indian Express report on private hospitals going MIA in this national crisis.

A survey finds that despite government exemptions, food prices went up because of supply chain issues. “Smaller cities have seen a much higher increase in prices with at least a few cities seeing a rise in retail food prices by as much as 20%,” write Sudha Narayanan and Shree Saha.

India needs a national employment guarantee, for rural and urban workers. Nikhil Dey and Aruna Roy in the Indian Express call for the state to guarantee livelihoods.

The Centre might refuse to listen to advice, but states have put together economic teams. Pallavi Nahata on BloombergQuint lists the economists who are advising various state governments.

The Reserve Bank of India hasn’t taken a position on monetising the deficit just yet. So says Governor Shaktikanta Das in this interview with T Bijoy Idicheriah and Kalyan Ram of Cogencis.

Despite the current drop in demand and supply, businesses fear inflation in one year’s time. So says this IIM-Ahmedabad survey, which showed a sharp spike in inflation expectations for March 2021.

“The lockdown has led to the suspension of normal politics… what is gradually emerging is a pattern of trust deficit in the state,” writes the BJP’s Swapan Dasgupta in the Telegraph. To be sure, he’s talking about West Bengal.

PRS has a collection of all 592 Covid-19 related notifications from Indian authorities so far.

And the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has a collection of case studies on Covid-19 responses, including India.

Can’t Make This Up

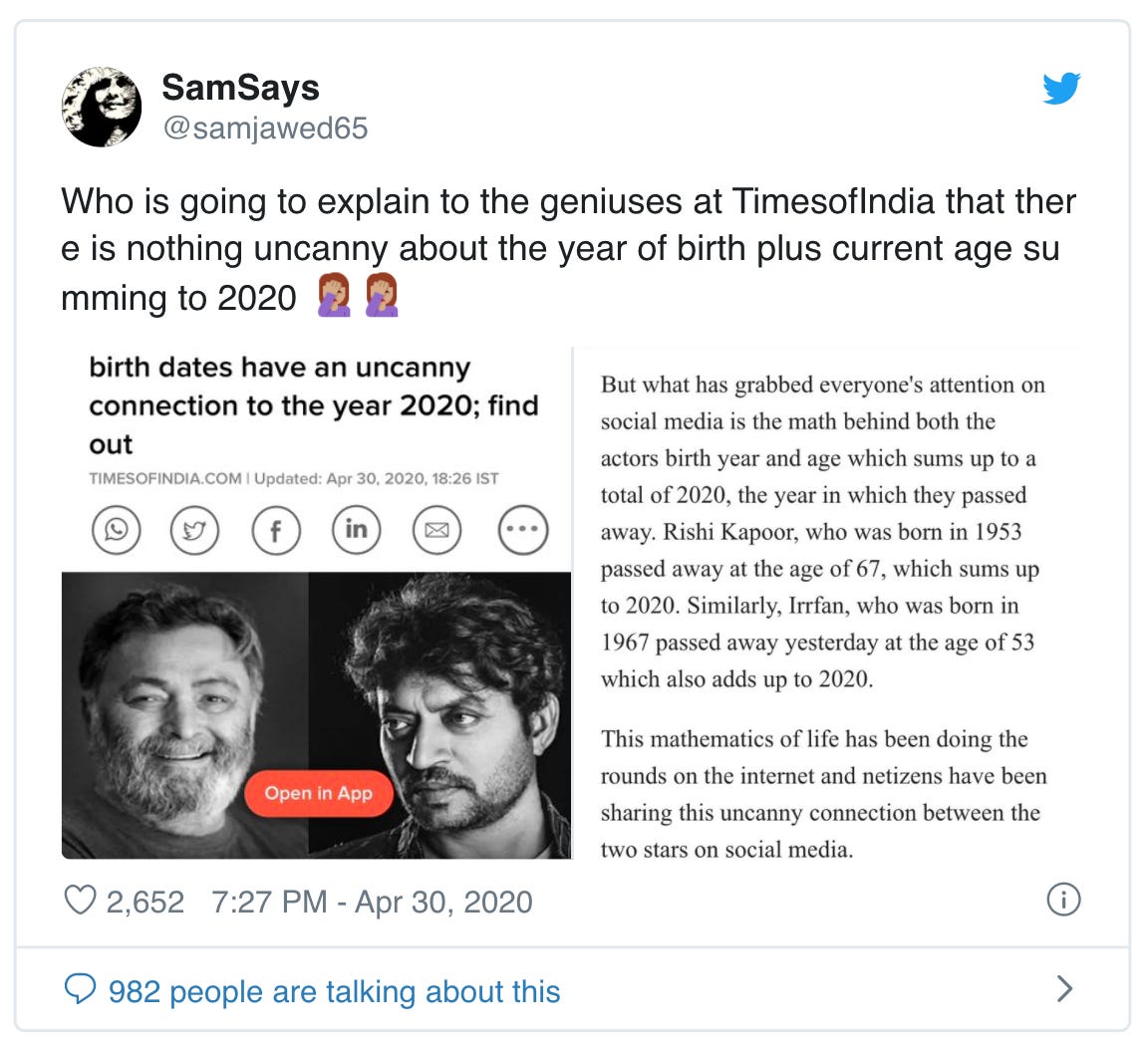

The Times of India is often made fun of.

You were expecting me to say, “but” there, no? Wrong.

The Times of India is often made fun of, because it does stuff like falling for a WhatsApp forward that claims, astoundingly that if you add your birth year to your age, you will get the current year – which is apparently proof that people who die have an “uncanny connection” to the year of their death.

If you found the Political Fix useful, please do share and subscribe. And if we missed any useful links or tweets, write to rohan@scroll.in